Making games is difficult. Making money from them is even more challenging, especially when price and value is a point of contention.

Games made by triple-A studios with hundreds of staff and budgets exceeding millions of dollars generally have standardised pricing points – although there is a push to increase prices alongside rising development costs.

Independent games aren’t afforded the same luxury of pricing uniformity, however. The price of indie games varies depending on many factors, including player perceptions of value.

To understand what goes into determining a game’s price, it’s important to know the major influences behind such tricky decisions. How much revenue each sale generates, the business development role of publishers, and the impact of popular subscription services are all major factors.

Developers of all backgrounds endeavour to make the best games they can under various conditions – but the business side of games can be just as challenging as the creative side.

How much do developers make from their games?

The distribution model for video games has changed drastically over the years. Floppy disks, cartridges, DVDs, and other forms of physical media were once the only way to access games. Now, not only have digital storefronts added more choice for both consumers and developers, they’ve become the preferred format; Sony’s previous financial year indicated 65% of sales were from digital purchases alone.

Although digital distribution allows developers to bypass the costly process of manufacturing physical media and having a presence in brick-and-mortar shops, there are still costs involved. With each digital copy a game sells, a cut is taken by its host platform.

The industry standard platform fee hovers around 30%, which includes the likes of Steam, PlayStation, and

Many game developers believe the standard 30% platform cut is too high. According to figures from the Game Developers Conference 2021 State of the Game Industry survey, 71% of over 3,000 respondents believed digital storefronts should only receive 20% or less of each sale.

One reason for this sentiment is that platform fees are only the beginning of the costs developers need to account for with each sale – even for self-published games.

Canberra-based developer David Cribb, who develops under the name ‘Colestia’, makes various games with progressive themes – including investigative thriller A Hand With Many Fingers, Game of the Year at the 2020 Freeplay Awards – and releases them on itch.io and Steam.

As a self-published developer, he receives between 70-80% of each sale through itch.io after the default 10% platform fee, payment processing, currency exchange, and other miscellaneous fees. Comparatively, Cribb typically receives less than 65% of each sale on Steam. It’s also worth noting his games all include a flexible pricing option on itch.io, allowing players to pay what they can afford.

‘I think that this form of pricing lets me make enough to survive, while the pay-what-you-want scale hopefully keeps the game accessible to people with low incomes,’ Cribb said.

Earlier in the year, Melbourne-based Ring of Pain developer Simon Boxer provided a general example on Twitter of how much game developers make, including rough figures for publisher arrangements and the Australian business tax rate of 30%. Although every situation is different, his calculations indicated that for every dollar of revenue, developers receive as much as $0.49 for self-published games, and as little as $0.245 for games published by a third party.

What goes into pricing a game?

One of the most difficult decisions any game developer can make is how much to charge for their game. The figures discussed above don’t capture the full picture either, with many different publishing and distribution combinations available. Team members and contractors need to be paid, in addition to costs associated with physical retail, classification, and other resources used throughout game development.

One industry veteran who knows plenty about the business side of game development is Jon Cartwright, who operates out of Brisbane as a consultant providing development and publishing support for games such as Modern Storyteller’s The Forgotten City, and the upcoming Innchanted from Dragonbear Studios. He told GamesHub that pricing games ‘is one of the hardest things I work on with developers’.

‘It’s a very, very difficult thing to try and quantify,’ Cartwright said. ‘Part of it is looking at the game, and then looking at the costs and the scope.’

Project scope is a significant factor in deciding a game’s worth. If a game takes a long time to make, it naturally needs to make more money to break even. Cartwright discussed the importance of sales forecasting in figuring out how many sales developers need to make at various pricing points to recoup costs. There are various resources online to help with the forecasting process, including a tailored spreadsheet created by Australian publisher Fellow Traveller, which was shared in an edition of the GameDiscoverCo newsletter.

Generally speaking for independent developers, Cartwright mentioned that if you need to sell a million copies, ‘something is wrong’. One strategy to avoid needing to hit the elusive million-copy milestone is to narrow the game’s scope from the outset, especially for first-time developers.

Another important step when deciding a game’s price is to identify the target market early in development. This includes researching what games already exist in the market, how much they typically cost, and what your unique value proposition is.

Such research helps to inform sales forecasting, project scope and budget from the outset, as it’s risky to figure out pricing points late in development, after spending years on a game that ultimately needs to sell an unrealistic amount to be successful.

Where do publishers fit into the picture?

Game development requires a lot of specialist knowledge and technical skill. To make a successful video game, business skills are equally vital. Not only do you have to make a game people want to play, but you also have to find a way to get the game to them in the first place.

This is where publishers become a factor.

Publishers help developers navigate the business of game development by offering various services such as public relations and marketing, negotiating with platform holders, and administrative work.

In exchange, publishers typically take a percentage of net revenue, which ranges depending on how involved they are with development and if they’re providing funding. Contract terms aren’t usually discussed publicly due to issues surrounding sensitive information and confidentiality.

Raw Fury, the Swedish publisher known for working on Sable and Backbone, made the surprise move of sharing the templates they use for negotiating contracts following the launches of its games. They revealed the company’s default revenue share is 50%; various developers who spoke with GamesHub indicated between 30-50% is fairly normal, although there’s not necessarily an industry standard, per se.

‘I’ve seen a lot of publisher contracts and it varies hugely,’ Cartwright said. ‘Sometimes it will vary based on how much money the publisher is putting into a game.’

‘If a publisher is not putting any money into a game – if they’re providing publishing, maybe localisation, [quality assurance], marketing, what have you – then broadly speaking, the developers are going to see better terms than if they were looking to have the publisher fully fund that title.’

Cartwright generally advises against signing the first offer tabled to developers, as it’s important to negotiate the best terms for the project. He also said that revenue split shouldn’t be the deciding factor in developer and publisher negotiations.

This is because additional services such as marketing and localising games into non-English-speaking regions potentially impact the ability to generate revenue in a major way. One local developer suggested that while a 50% publisher cut may seem steep, they do 50% of the work in return, freeing up development staff to focus on the work they specialise in and enjoy.

When pitching a game to publishers, Cartwright recommends developers include a suggested retail price, which helps a publisher view where it fits in their portfolio.

‘Have your value proposition worked out,’ he said. ‘Know what you believe the game is worth and know why you think it’s worth that.’

The Game Pass effect

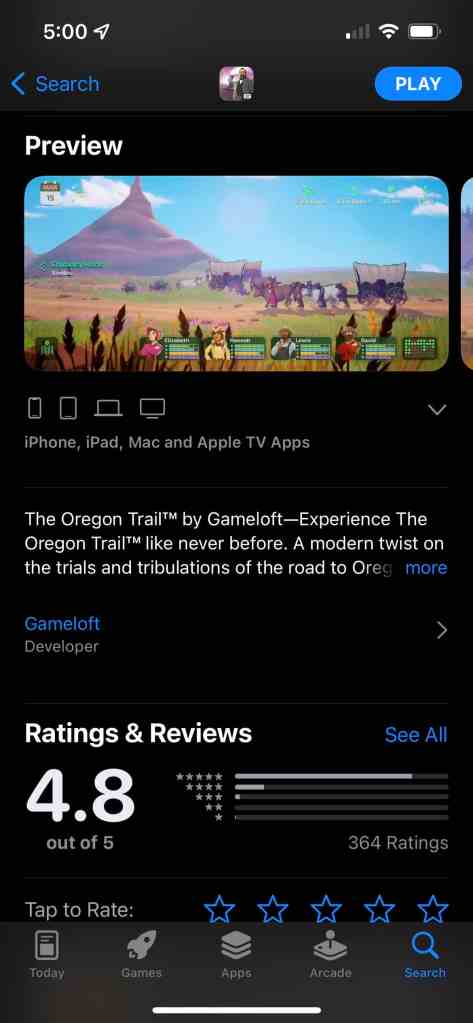

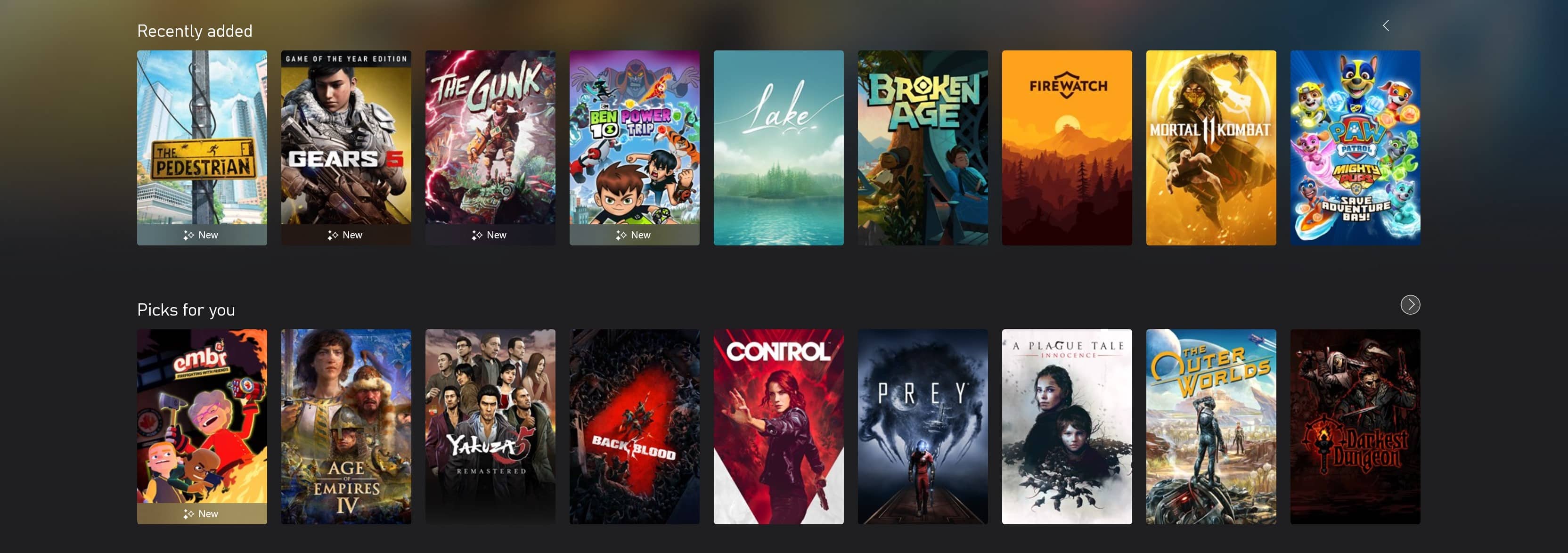

With the popularity of on-demand subscription services such as Xbox Game Pass and

Such services offer clear value to consumers, providing access to a library of games for a reasonable monthly fee. Does it negatively impact retail sales, however?

In short, no: quite the opposite, it seems.

Anecdotes from multiple Australian developers whose games have been on Xbox Game Pass indicate having a game on a subscription service is a positive move, especially for multiplatform titles.

‘Everything I’ve seen in our experience and for friends as well: Game Pass doesn’t cannibalise on your existing sales on other platforms because everyone’s quite siloed,’ one developer told GamesHub anonymously. ‘Very few [players] own multiple consoles, even more so in this generation where they’re hard to get.’

‘If you’ve got millions of players playing [your game] on Game Pass, and they’re telling their friends who don’t have an Xbox “hey, I played this game, it’s really cool”, that kind of word-of-mouth generates sales elsewhere.’

This trend was confirmed by multiple developers, where being available on one platform’s subscription service saw a boost of sales on another platform. It also aligns with IGEA’s research, which found 67% of surveyed households preferred to buy games on release, rather than play them on a subscription service.

How games land on subscription services

Chris Wright, Founder and Managing Director of Fellow Traveller, shared with GamesHub what actually goes into getting games such as Neo Cab and Genesis Noir on platforms such as

‘Business development and seeking out commercial opportunities is a significant part of what we do for games on the label,’ Wright said. ‘The first step is looking at what opportunities would suit the game and then, of course, pitching to try to secure those opportunities. This starts well before launch, but is also something we’re doing constantly after launch as well.’

‘We have portfolio meetings with the platforms and stores we work with a couple of times a year. In those meetings, we present our upcoming game lineup and talk about potential opportunities such as Game Pass. Where there is interest in a game from the service we would then pitch it in more detail, and the team at the service consider it and make an offer if they want it.’

Each platform has a different way of operating, but many subscription services reportedly offer a flat one-off signing fee for a game to be available for a fixed duration, with additional incentives provided for the most-played games. Specific dollar amounts of deals are highly secretive, but allegedly vary drastically from game to game.

On some of the deals for subscription services, one developer shared they had ‘seen numbers that are higher than I ever would have imagined for a certain type of game and other ones that are lower – like they got low-balled’. They added that negotiating for platform deals is an important part of generating revenue to survive, in addition to the marketing it provides.

Earlier in the year, as part of the legal proceedings between Epic Games and

Interestingly, Apple’s early spending acquiring games was reportedly reigned in following a shift in

With current market trends, developers see subscription services as additive to selling games at retail, not competing against them, which Wright described as ‘an important additional revenue stream alongside regular sales’.

‘Overall we’re fans of these services both for the financial benefits and also how they help indie games reach more players,’ he added. ‘Indie game development and publishing is highly risky as you just don’t know what a game will sell before it launches. When buy-outs are involved, that can really help de-risk a game by providing some guaranteed revenue.’

‘Subscription services also lower the barrier to players trying something new and different, and that is really valuable for indie games, especially more unusual games like the ones we like to publish. A whole bunch of those players end up bouncing off your game or leaving one-star reviews because it’s not to their taste but there are also a lot of people that would never have bought your game giving it a try and loving it.’

Cartwright also pointed out ‘both Xbox Game Pass and

Where is the value in a video game?

By now, it’s clear there are many factors at play when pricing a game. Despite the many hours of expertise required to make and release games, some audiences equate value to a nebulous dollar-per-hour ratio.

When Cribb launched A Hand With Many Fingers, he set the price of US $10 (AU $14), only to halve it less than a month later.

‘By that stage, there were a bunch of negative user reviews on Steam complaining about the length,’ Cribb said. ‘Interestingly, I didn’t get those same criticisms on itch.io – when the Steam user score was sitting around 60%, the Itch score was around 90%.’

‘I think that difference partly comes down to platform design. Steam doesn’t allow for pay-what-you-want pricing, so players are taking a bigger risk when they purchase something experimental at full price. Steam also offers full refunds where a game has been played for less than two hours. That definitely makes some people think that a game is worthless if it’s under 2 hours long.’

On the concept of equating a game’s value to its duration, Cribb is unequivocal.

‘I hate it. The simplest way to ruin a game is to pad its runtime so that it offers more “value for money”.’

When GamesHub asked Cartwright how the perception of value in games has changed throughout his lengthy career, he made several main observations.

One is that independent games are often compared alongside triple-A titles made by large teams, skewing their perceived worth. He stressed that the value of video games is ‘not a linearly sliding scale…to hold [indies] up against triple-A games’. ‘I don’t think that’s a fair comparison.’

With digital storefronts taking precedence over physical, deep discounts are common later in a game’s life. ‘Unfortunately, one of the trends is that we’ve all been educated into waiting for discounts, and expecting them,’ Cartwright lamented. Plus, he believes players now view ‘paying for [a game as] just the start’, with the expectation that developers will provide post-launch updates well into the future.

Value has changed, and will continue to change. Going forward, the most important thing to remember is a game’s price is far more than its contents; it represents the labour, tangible and intangible, of the many people who pour themselves into their art.