Australia has a long history in the video games industry, one that’s often gone unrecognised despite its cultural significance. While local government is slowly acknowledging the value of games, years of neglect has seen great swathes of Australian video game history vanish without a trace. While modern titles like Unpacking and enduring classics like L.A. Noire have achieved the accolades and longevity they deserve, a lack of structured support and poor preservation has seen several, historically-significant projects fall through the cracks.

These are the Australian-made games you’ll never play; the ones so close to completion, they almost saw the light of day. Games that collapsed without major funding, projects that were too ambitious, or were just ill-timed. The ideas that went viral, and never got the attention to back them up.

While cancelled or incomplete video games are often dismissed as failed ideas or tantalising ‘what ifs’, they occupy an important part of gaming history. They represent years of talent, labour, technological change, and ideas that define an era. They also represent opportunity. With no closure, it’s easy to wonder whether these titles could have changed Australia’s gaming landscape.

As cultural artefacts, cancelled or unrealised games can tell us so much about the circumstances of their era.

Interzone Futebol tells a tale of mismanagement

Interzone Futebol was a realistic soccer MMO in development at the Western Australian branch of Interzone Games in the early 2000s. The studio was US-based originally, but split itself across multiple continents as its business grew. With investors looking to capitalise on the growth of the MMO genre in this period, Interzone Futebol entered production in Perth.

‘Basically, it was a soccer MMO,’ said Simon Boxer, developer and former Interzone employee. He worked on concept art for the game, as well as graphic design and environmental art. ‘It had some design troubles over time, and it didn’t really have a clear path to launching.’

The game was based in a hub world designed to resemble Rio – a sort of proto-metaverse – where players could run around and interact with each other. Then, they’d be able to enter a matchmaking mode and play a full team in traditional soccer games. Along the way, they’d earn special ‘stances’ which could change how they could play the game.

Despite largely featuring traditional soccer gameplay, Interzone Futebol was built on the Big World engine, the same one designed for MMO-style adventures, and currently powering Wargaming’s World of Tanks series.

‘For a soccer game, it probably wasn’t a great fit, because you want low latency,’ Boxer said.

This rocky foundation, and a lack of ‘compelling’ ideas meant Interzone Futebol never saw the light of day. The first signs of trouble, according to Boxer, were a lack of communication from management and overspending on the company dime – allegedly, an expensive private jet was frequently used by leaders at the company. This was despite major cash flow issues being passed onto developers.

While Boxer noted the studio environment at Interzone was fun, and had a ‘really good’ vibe, it was ultimately money troubles that brought about the end of the project, and of Interzone in Perth.

‘We’d be working for months at a time, and then get paid back as [the studio was] having cashflow issues,’ Boxer explained. The Perth team had heard of similar troubles in China and Brazil, but had no option other than to keep working.

It all culminated in Interzone flying in employees from Big World to strip and upload the data from the Perth Interzone studio, with all the work they’d done being taken while staff were locked out of their physical offices. The IP was later sent to Ireland, with the Perth studio being unceremoniously shut.

In its wake, Interzone reportedly left a $1 million debt to the ATO, as well as a $500,000 IOU to staff.

Boxer departed the company ahead of this final closure, and has since gone on to produce several independent games, including Ring of Pain and the upcoming The Dungeon Experience alongside Jacob Janerka. But he’s always remembered the lessons working at Interzone taught him, particularly when it comes to sturdy management.

‘The biggest thing you can do to benefit your team in your projects is scope small from the start, because as you develop, you unravel the project and realise how big it really is,’ he said.

Read: Simon Boxer’s personal Ring of Pain: The long road to games success

Interzone Futbol was a game sunk by its own foundation, and the wide scope of Interzone’s ambition. In an era when MMO projects were becoming increasingly popular, it represents a wild attempt to capitalise on the success of the popular genre, to no avail.

It wasn’t the only cancelled Australian title looking to take advantage of the growing interest in MMOs during the 2000s.

Sega Studios Australia was developing a PlayStation Home attraction

In the late 2000s, major companies were hedging their bets on MMOs – much like modern companies of the 2020s are looking to invest in large scale ‘metaverse‘ worlds. As gaming technology became more accessible, there was an increasing push to ‘gamify’ social interactions by providing players with evolving, realistic worlds they could occupy.

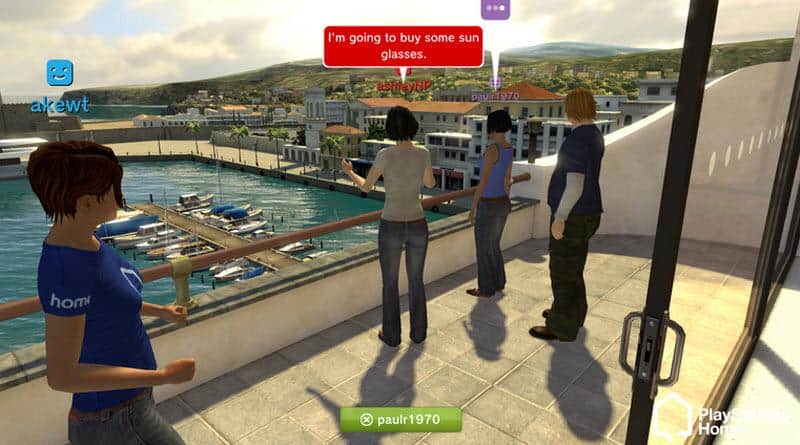

PlayStation Home was one of these rising MMOs; a world where players could dress like their favourite characters, roam a 3D world, gather accessories, and build their own unique spaces. At its peak, PlayStation Home boasted a player base in the ‘several millions‘, with dedicated players returning on a frequent basis to engage with new content and chat with friends.

The popularity of this world soon attracted developer and publisher Sega, who wanted to carve out a piece of PlayStation Home real estate for a Sega-themed attraction. To that end, it tasked the team at Sega Studios Australia with building out a space in this digital world.

‘The ambition was to try and build something that would tie the different properties of Sega together and give people a social space to engage,’ Sanatana Mishra, former developer at Sega Studios Australia (and co-founder of Witch Beam) told GamesHub. ‘We were trying to build this entertainment hub, almost like a theme park within a game.’

If that sounds familiar, it’s likely because Bandai Namco recently announced it wanted to create its own $182 million metaverse, based on a very similar concept – a world in which the company’s video games could form the basis of an interactive, community-based world. When it comes to the metaverse, everything old is new again – and Sega’s designs on a PlayStation Home hub world proves just that.

‘It was very much an early version of that concept of bringing everybody’s properties together and sharing stuff. PlayStation Home didn’t quite understand where things were going with user generated content in that regard,’ Mishra said. ‘This was all very much high tech stuff – you needed to be a “full on” game studio to even consider building something in PlayStation Home. [It was] quite technically difficult to build content for.’

Mishra described the project as one of the most fun projects he’s ever worked on as a core designer. His job was to build on the bricks of PlayStation Home, coming up with new ideas for Sega-themed mini-games and activities players could interact with.

‘[It] must have been five or six of us at Sega, with support from people in Europe, and we were just cranking out all kinds of cool stuff, and getting models from games, and cutting them down and making them appropriate for use in the space,’ Mishra said.

‘We had this whole plan for a big extended theme park with lots of different rooms that you could go between … we started developing these massively multiplayer mini-games that I think 48 players could play, which at the time was massive.’

But despite the team having prototyped several games, the Sega world for PlayStation Home was soon cancelled. Even years later, Mishra doesn’t completely understand why.

‘The reason the project died … is still a mystery to me,’ Mishra said. ‘My understanding – and this is a great example of just how complicated projects can be – is that it died due to people not understanding what it would be used for … how it would be financially viable or useful.’

As a concept ahead of its time, Sega’s planned PlayStation Home world could have functioned as an early metaverse, one which connected Sega fans in an engaging, virtual world – one that sounds heavily inspired by the defunct Sega World theme park in Sydney, Australia.

While Mishra believes the concept was cancelled because of this lack of understanding about its purpose, he also agrees it’s a project that has intrinsic value to the modern day. Its cancellation speaks to a lack of clarity around the purpose of metaverses in the early 2000s, but also highlights just how far technology and common sentiment has turned around.

With management ultimately failing to see the application for a Sega proto-metaverse, assets for the game were quietly set aside – the specialist nature of the PlayStation Home engine meant nothing could be reused – and the team moved on to other projects, some of which were similarly cancelled.

But despite this project sinking under its own weight, it remains an important artefact in global gaming history. It goes to show that sometimes, all it takes is bad timing or whims for a project to be cancelled.

Oceanic Studios had nearly finished an Impossible Mission remake on GBA

In 2004, Melbourne-based developer Oceanic Studios acquired the Epyx license from Ironstone Partners, with the intention of remaking Commodore 64 classics Impossible Mission, California Games and other titles for the Game Boy Advance.

According to studio co-founder and CEO Beau Barnett, the planned remake of Impossible Mission was 99% complete before Ironstone Partners pulled the plug, selling the Epyx catalogue to Eidos and cancelling Oceanic’s development contract.

This decision came despite Oceanic staff self-funding a trip to the UK to secure the rights to the game, as part of a Victorian Government ‘trade mission’ designed to highlight the skills of Australia’s local video game industry. It also came despite Oceanic Studios having a near-fully functioning game.

‘It was cancelled right away, almost with no notice,’ Barnett told GamesHub. ‘I was pretty forlorn. But I was happy that I [and Oceanic] had gotten to that point.’

Barnett remains proud of the work the team did on the title, and describes the cancellation as a good learning experience to have. The unfortunate reality is the rights to the franchise changed hands before Oceanic’s efforts could ever be seen by the public; a consequence of the ever-changing nature of the games industry.

Still, the semi-completed game stands as a testament to the skill and effort of Australia’s local developers. Footage viewed by GamesHub was very promising, and showed off a polished game that could have been a side-scrolling hit under different circumstances.

Despite the ultimate fate of the title, Barnett believes it remains an important part of Australian gaming history.

‘I think it’s really important,’ he said. ‘[Impossible Mission is] a very famous game. It’s got a great legacy. And the fact that it was done Australia … it was very iconic.’

The idea was sound enough that Impossible Mission was eventually remade, in the hands of developers System 3. This version was later ported to the

A case of bad timing and reneged contracts meant that Oceanic soon moved onto other games, and left Impossible Mission locked away, alongside assets for other unreleased games. As Barnett made clear, this was a far different era in video games, particularly for Oceanic, which was still finding its feet in a burgeoning industry.

As a stepping stone to later success, this cancelled Impossible Mission title is an important footnote in the history of the company, and the history of Australian games.

Even surefire winners like a Seinfeld game can evaporate

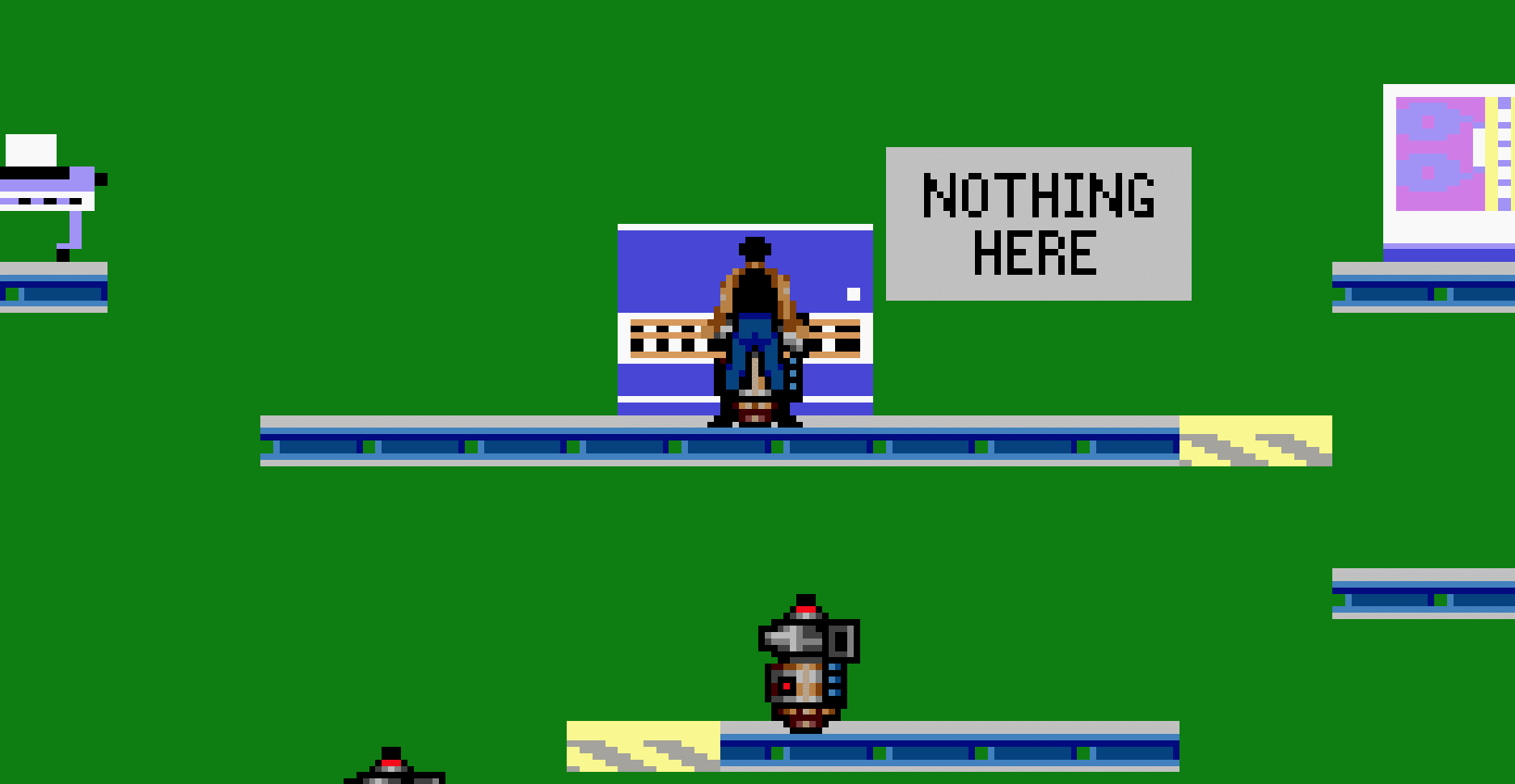

Unlike other games on this list, Seinfeld Adventure was never actually approved for development. Instead, it existed in the nebulous realm between fan game and semi-serious pitch, with developer Jacob Janerka playing around with the idea at first, and ultimately deciding to pursue it with the encouragement of friend Ivan Dixon, who works as an animator and director.

Seinfeld Adventure was designed as a point-and-click adventure set in the world of classic sitcom Seinfeld. Players would be able to take the reins of classic characters and guide them through a number of funny scenarios. What started as a fun project soon morphed into a more serious one for Janerka, who noted the positive reaction to stills of the game posted online.

‘As the buzz was insane every time I posted it, I began to think there was some legitimacy for the project,’ Janerka told GamesHub. ‘At one point I was actually contacted by an LA advertising company to make the game for a big marketing push.’

While this interest soon ‘fizzled out’, his passion for the project and its potential legitimacy was reignited with the help of Dixon. While they both knew the game being picked up would be a long shot, the virality of the idea fostered hope for the future.

‘We had famous names retweeting it such as Mark Hamill, Elijah Wood and we were only missing Daniel Radcliffe to complete the holy trinity of protagonists,’ Janerka said. ‘We even went through the official channels with real life LA agents. However none of them led to any of the cast or anyone official acknowledging it or contacting us.’

It was ultimately the risk of legal issues that forced Janerka to abandon the project, with multiple people messaging him privately to warn he could be thrown a ‘cease and desist’ if he chose to continue without the support of the official Seinfeld IP holder (which appears to be distributor Columbia Pictures).

After the final, viral pitch for the game failed to deliver any official leads, Janerka chose to pack away the project, with the assets being stored on backup hard drives in an ‘undisclosed location’. While he remains ‘stoked’ with the project and hopes it does see the light one day, he acknowledges that complications behind the scenes will likely prevent the game from ever being born.

As it stands, the final trailer remains the only testament to the work of Janerka, and how the world of Seinfeld Adventure came to be unrealised.

The potential for the project certainly shows off the developer’s talents and quirky humour, but it also shows just how quickly good ideas can collapse without appropriate support, and pitch-perfect timing. Even raving demand is not enough to save some video game ideas from cancellation – even when that ‘cancellation’ is more of an unofficial stoppage.

It’s yet another footnote in a vast history of unreleased Aussie-made games.

Australia video games history is peppered with tales like these – stories that are important, but rarely shared due to a perceived negativity around cancelled games. Several companies contacted for this article chose not to respond, or declined to be included – with one willing party having to pull out due to a management directive. But cancelled games aren’t something to be ashamed of – they’re a natural result of an ever-changing games industry.

Trends often dictate what video games are developed. Whether it’s MMOs in the early 2000s, or the modern popularity of the open world genre. Sometimes, games arrive too late. Sometimes, complicated business dealings, money troubles, or a simple lack of attention can lead to a game being sunk – but these cancelled video games all serve as reminders of why preserving video games history is important.

Not only can cancelled games reveal more about the whims of the video game industry, they can also showcase the talents of local developers, changes in technology, and reveal how both players and developers understand the gaming world. In the 2000s, the idea of ‘Sega metaverse’ was derided and misunderstood. In 2022, Bandai Namco is establishing a world with the same goals.

These are important touch points in charting the evolution of gaming. As ever, learning from the past remains an essential part of moving forward and innovating for the future.