I have a set of two postcards which hang on the back of my front door. They’re different depictions of the bible story of Judith beheading Holofernes: one by Caravaggio, and one by Artemisia Gentileschi. In Caravaggio’s version, Judith leans daintily away from the beheading at hand; her pose is unnatural, almost languid. Gentileschi’s Judith puts the force of her entire body behind the blade, her brow furrowed in focus. Despite these grand and violent scenes, they remain domestic and homely in travel-sized, tourist-y form: postcards dangling precariously from rationed Blu-Tack.

Occupy White Walls is a game where you can build your own gallery space and fill it with works of your choice. A growing library of hundreds of architectural assets are available to customise your own space, and thousands more artworks – mostly drawn from public museum collections – are available to hang as you please. You can also chat with other players and visit other custom galleries.

I was excited to place the two depictions of Judith within the game, in full size, in a space of my own imagining. My trivial little piece of curation could finally become dignified in a gallery space.

Building a better digital gallery experience

Occupy White Walls’ strongest feature lies in its capacity to evoke a sense of place. By allowing players to customise not only an interior space, but also the area outside of it, the gallery inhabits an environment. Galleries can float listlessly in the middle of a great lake or stand loud and littered on a busy street corner. Our experience of visiting the gallery means that our arrival and departure can be physically manoeuvred from outside to inside and inside to out, rather than simply being plonked into a museum lobby.

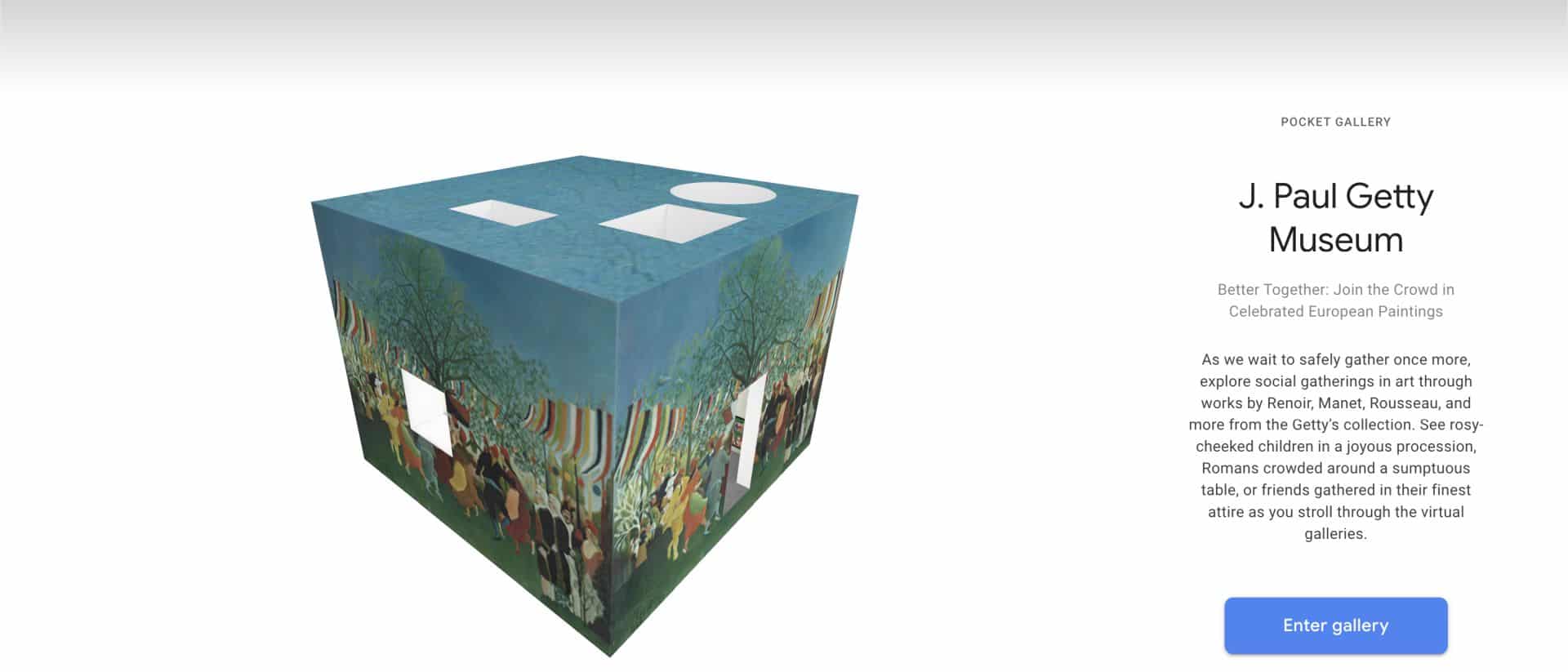

This stands in contrast to the virtual galleries we have, until now, become accustomed to seeing: though digitally rendered like OWW, Google Arts and Culture’s virtual exhibitions exist in a void. When we arrive at the website, we can examine the gallery space from the outside, like turning a Rubik’s Cube over in our hands: this online exhibition is an object, not a place. And when we click ‘Enter gallery’, we are scooped up and swooped into the beginning of the exhibition. There’s no mystery in that – and so, my curiosity for the exhibition space disappears as I appear within it.

In Occupy White Walls, the visitor starting point inside your gallery is dictated by you and where you choose to place your desk. Curation, then, is not only about what artworks you choose to display and how you display them, but also about sculpting the visitors’ experience of arriving at your gallery.

Part of the strong sense of place in Occupy White Walls is thanks to its redefinition of what a gallery space looks like. The assets in OWW lean towards maximalism. This is perhaps a fault, as the result of these assets are often designs exceedingly focused on spectacle and less on art, echoing recent trends in ‘Instagram traps‘ and ‘immersive art experiences’.

But these maximalist tendencies reveal quite quickly how OWW challenges ideas of what a gallery should look like. The white cube takes a back seat to galleries that look like Jazz bars, artist studios and public gardens. Some galleries even mimic domestic environments; small apartments just like my own. Suddenly, my trivial little piece of postcard curation feels validated. Domestic and homely becomes a completely acceptable – even normal – environment for a gallery.

Here we see the democratisation not only of art – freely available to players to use as they please – but a recapitulation of the democratisation of curation we’ve seen over the last few years of the Internet. Finely-tuned Instagram and Pinterest feeds, post-ironic and acutely local meme accounts, Tumblr art accounts, Depop resellers and Twitter bots are all recent iterations of the Internet curator.

Sometimes we consume content, hand-picking the very best and reposting it within our specific contexts. Other times, we design bots to pick at random, creating a Rorschach blot of comparisons and reinterpretations for each person who views them.

Some artists have made this online curation part of their practice. James Bridle, artist and journalist, curates what he dubs the ‘New Aesthetic’ on his Tumblr, choosing images which begin to exhibit an aesthetic of the future: a ‘mood-board for unknown products’.

OWW takes these trends in curation and makes them explicit.

OWW has been in early development since it launched in 2018, so it has its kinks. The UI is ugly. Assets are easy to misplace, so building can be an arduous task. And while it’s a great thing that artworks can be uploaded by anyone, there is still no way to filter out amateur erotic photography.

That, after all, would be a minefield for OWW regarding the definition of art and the place of censorship.

But it nails the fundamentals.

OWW embraces the hybrid body that was missing from the first-person perspectives of virtual exhibitions I’ve examined before. In third-person, we get an embodied sense of the body’s relation to the space around it. This is only improved by the game’s commitment to more-or-less to-scale artworks: the spatiality assumed by the player’s body allows us to understand the real-world impact of the painting. If we want to view the work up-close and in detail, we only need to click on the artwork so that it expands to the full screen view. And, unlike the isolatory, echoing halls of the Klimt vs Klimt exhibition with Google Arts and Culture, in OWW, the social is vindicated as a key part of the experience of visiting a museum – as it is in real life.

Read: God, give me a body: How virtual events and museums can be better

I can see Occupy White Walls becoming an incredible learning tool. Museums and art galleries could use it as a supplement to their own virtual exhibitions, inviting students and general audiences alike to engage in their online collection with active interaction and a critical eye.

Art can then be truly democratic: allowing for anyone to make an intervention in the museum collection, interrogating, perhaps, its colonial origins, or its lack of representation of women and BIPOC artists, or resuscitating new meaning from rarely-seen and often-misunderstood artefacts. With some minor updates, Occupy White Walls could become the newest frontier in the democratisation of art since the age of mechanical reproduction.

Occupy White Walls is available in Early Access on PC via Steam.