Have you ever had a game you’ve been unable to put down, until you cleaned up every trophy? Or are you one of the dedicated few that picks games up purely for their achievements?

If that’s a Venn diagram, I’m in the middle. My engagement varies by game: in March, I bought Elden Ring and refused to stop playing before I’d earned all the PlayStation trophies – system-level awards for achieving particular tasks, and even synchronising my killing of Malenia, Blade of Miquella, with the Platinum trophy – the final trophy that proves you’ve earned all others. More recently, I found a copy of Call of Duty: Vanguard on sale, so I picked it up purely for the largely campaign-centric trophy list, which I cleaned up in a week and half.

These big blockbuster games get plenty of trophy-driven foot traffic – but there are some dark horses in this achievement race. In my scrawling through trophy websites and forums, I’ve noticed guides for Australian indie games like Webbed and Moving Out with thousands, even tens of thousands of views.

Much has been said about the serotonin-driven completionist drive of trophy hunters, but I wanted to hear from the other side – from local developers, on their understanding of achievement ecosystems, and how they approached design and implementation in their own games. Taking stock of recent Australian indie releases, I wanted to see how, on a national scale, these games stacked up against other more popular international releases, against these dominant modes of playing.

During Melbourne International Games Week 2022, I spoke with Australian game developers who had recently released games – Cult of the Lamb, Justice Sucks, Heavenly Bodies and Wayward Strand – to discuss not only their implementation and inspiration, but to gauge the weird and wonderful ways they’ve played with what achievements can do for their games.

Completion of the Lamb

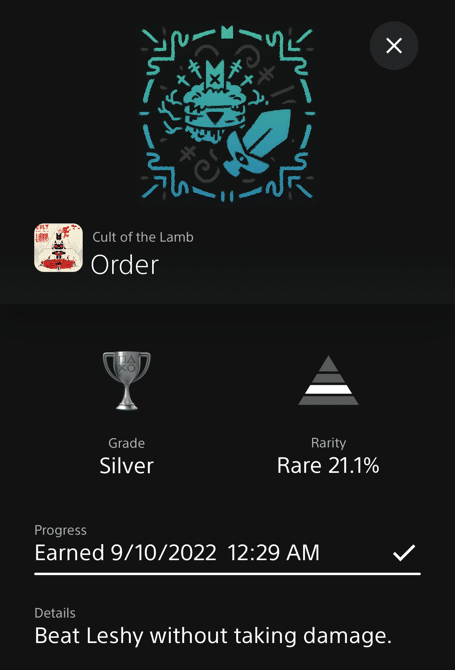

Base building-roguelike hybrid and breakout indie hit Cult of the Lamb has a relatively standard achievement list. Within, you’ll find achievements for beating big bosses, for unlocking all of a certain item, and for fully upgrading the various facets of your base, most of which you’ll unlock through regular play. Achievements also extend the game’s farcical tone: ‘Cannibal’, for example, requires you to cook a meal from the meat of one of your followers – out of context, an odd impression, but totally in line with the comedy of the game.

Though Cult of the Lamb may be relatively short and simple, as Massive Monster developer Harrison Gibbins tells me, the achievements extend the game’s length beyond a basic level of completion. ‘Cult of the Lamb’s playtime is roughly 10 hours to beat the main story, though with achievements I’d say that would almost be doubled.’

Unlike some games, Cult of the Lamb has no difficulty-specific achievements. You’re not required to beat the game on ‘Very Hard’ to round out your list – ‘Easy’ will suffice – though that’s not to say the achievements offer players an obstacle-free playthrough. Paired with standard markers of progression for beating each of the game’s dungeon leaders (‘Speak/Hear/Think/Do No Evil’) are achievements that require you to beat each of them without taking damage, a potential roadblock for interested parties.

Key to these damage-less achievements is an added element of replayability, an extra layer of challenge for devoted cult leaders. But their implementation is also tied to the game’s accessibility: ‘We made sure we had ways to refight bosses so players didn’t have to restart the game to complete that achievement.’ There’s nothing more devastating than checking your progress against an achievement guide and realising how many collectibles are missable or how many checkpoints you’ve progressed beyond.

‘It was important not to make too many [achievements] based on combat or difficulty, so they were accessible to all players.’

Achievement Communities

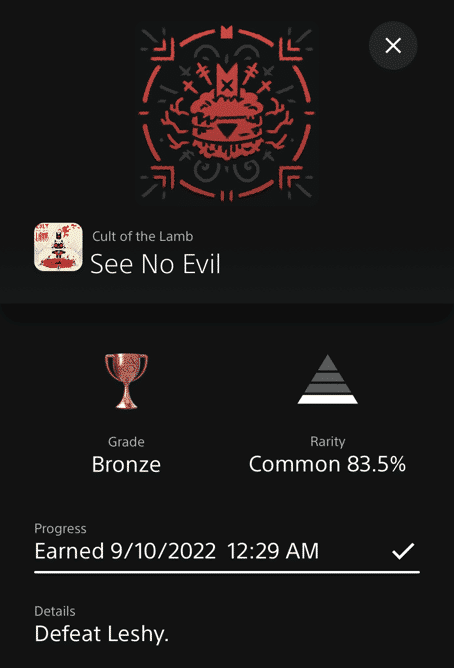

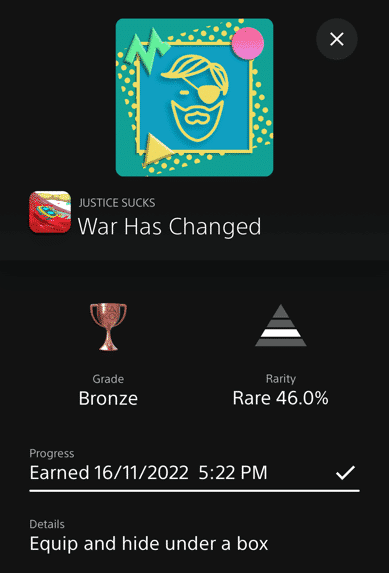

Compared to Cult of the Lamb, a game like Samurai Punk’s Justice Sucks provides a more complex achievement list. Within the context of the experience, Creative Director Winston Tang acknowledges that achievements are a great way to add extra value to the game. ‘You can have a bit more fun with them because they’re inherently breaking the fourth wall.’ Because of their placement outside of the game, achievements are used mainly for tongue-in-cheek moments, as jokes, to add extra lore, or as incentives to purposely ‘break the game, or play the game not as originally intended’.

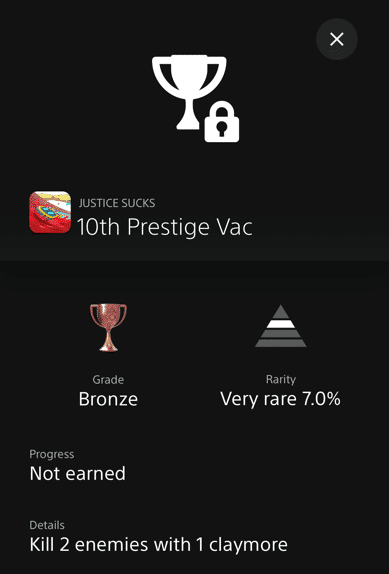

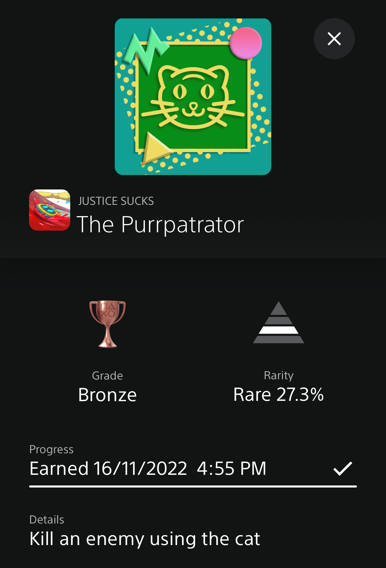

With Justice Sucks being a sandbox of sorts, this ethos works well, and encourages a full fleshing out of the game experience – the achievement list asks you to kill in clever or unexpected ways. For example, ‘Shaken, Not Stirred’ requires you to kill three enemies with a single ‘bartender bot attack’, and ‘The Purrpatrator’ asks you, simply, to ‘kill an enemy using the cat’. Other achievements are more referential: for ’10th Prestige Vac’, you’ll need to channel your former teenage Call of Duty self to get a double kill with a claymore, ‘War Has Changed’ asks you to ‘equip and hide under a box’ – the achievement tile fit with an allusion to Solid Snake of the Metal Gear series.

It’s reassuring to hear that as a developer, Winston is aware of the oft-bloodthirsty drive of the achievement hunter. ‘We know for a fact that people will also just buy games to get the achievements and trophies.’

In response, I plead guilty – in the week before talking to Winston, I’d just bought Roombo: First Blood and Feather, two of Samurai Punk’s previous smaller games, both with platinum trophies that guides had suggested were achievable in under an hour. How could I resist?

These two games differ greatly in experience and gameplay, however, and Winston sees them as good examples of how achievement design should follow the values of the game. Roombo, a test-drive for Justice Sucks, is very much a checklist game in and of itself. Sans achievements, the game already wants you to check every box it’s offering you, and you’re likely to knock out the majority of achievements through basic gameplay.

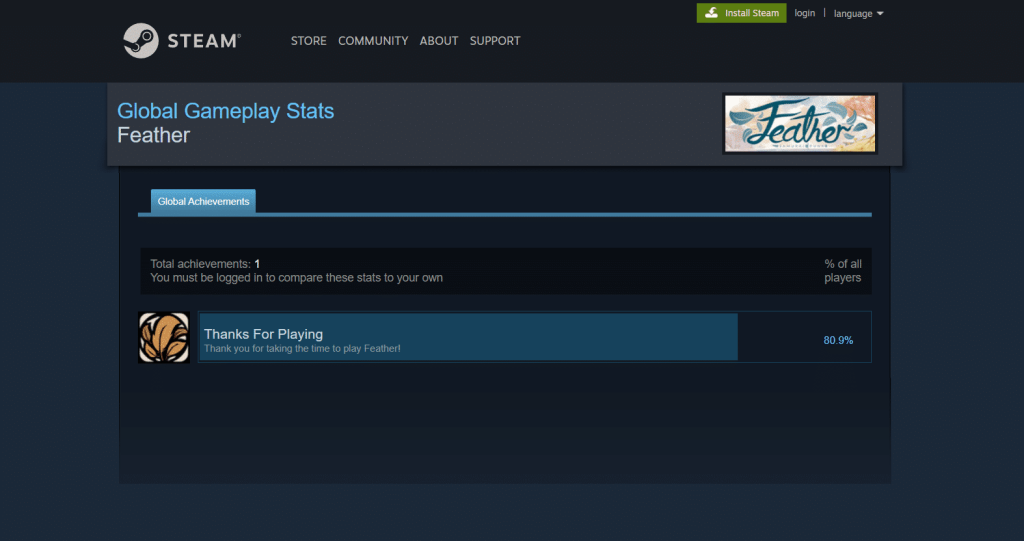

Comparatively, Feather, a meditative game where you play as a bird and explore a picturesque island, is about ‘intrinsic fun and reward’ Because of this, Winston says it was a conscious decision to only include one achievement on Steam: ‘Thanks For Playing’.

Both PlayStation and Xbox boast more lively achievement ecosystems, and the list was expanded for these platforms to include a variety of miscellaneous avian tasks. Achievements were designed to be encountered more naturally through experience and exploration, so to maintain the game’s observational tone, they’re all ‘hidden’ by default – their name and description are concealed from the player. (Figure out how to unlock them, however, and you’ll notice the lyrics to one very specific and iconic Nelly Furtado song).

Winston believes there’s real value in the community that’s come out of achievements becoming standard practice in video games. Popular trophy guide and achievement tracking sites like PSNProfiles, PlayStationTrophies.org and TrueAchievements are all community-run, and the extensive guides made by high-profile creators PowerPyx and PS5Trophies come from a real place of passion.

Certainly, I admit, there are games I wouldn’t have played nor even heard of, if not for the guidance of these invaluable resources.

Winston says it was feedback from this community that led the team to reduce the necessary requirements for more time-consuming achievement. ‘It was one of the achievement reviewers that pointed out that all achievements are good, except for this one, which is mega grindy’. The trophy in question is ‘Blood, not funny!’, which requires you to ‘Consume 6666 litres of blood’ – a sensible amount for any robot vacuum.

Thankfully, these stretch goals are a far cry from the ludicrous requirements of something like the asymmetrical multiplayer game Friday the 13th, which has achievements that require you to play 1000 matches as both Jason and as a counsellor. ‘For us, we want to make it challenging, but not fucking stupid’, Winston admits.

The PlayStation Plus Bump

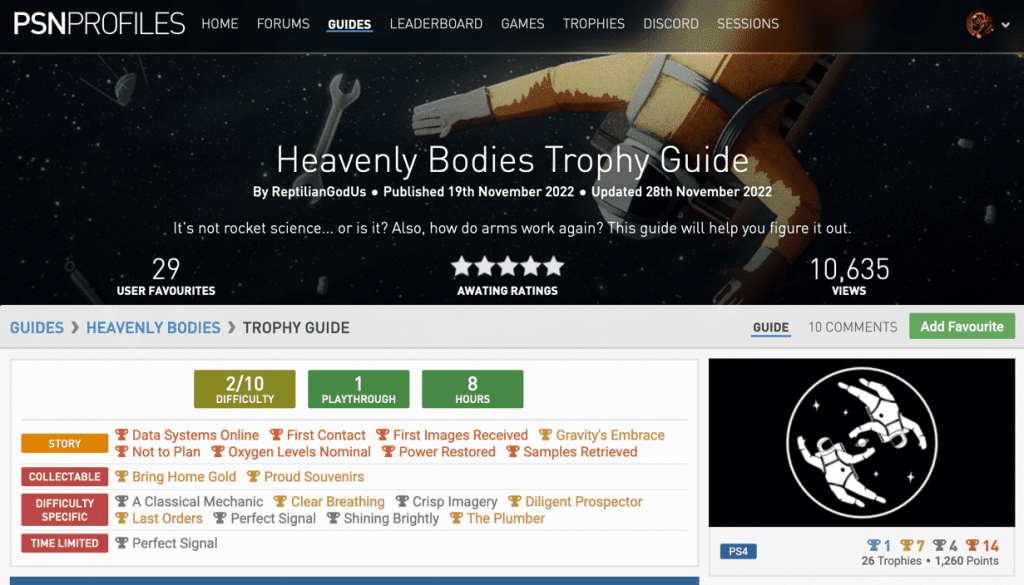

Heavenly Bodies, the finicky, physics-based astronaut puzzle game developed by 2pt Interactive may have been released in 2021, but its recent arrival on the PlayStation Plus subscription service, as a complimentary game for its Essential subscribers in November 2022, bears consideration.

From my time in trophy-hunting forums, I know there’s a strong community drive for PlayStation Plus-subscribed trophy hunters to give each of the monthly games a crack, especially the ones that may be smaller or shorter than other games on the line-up. For the November 2022 line-up, Heavenly Bodies sat alongside Nioh 2, which trophy guides estimated would take upwards of 100 hours to earn the Platinum.

By design, these subscription services propel a focused and renewed attention to non-new release games, and games included are often followed by achievement guides. During November, Heavenly Bodies not only charted on the ‘Popular Now’ list on PSNProfiles – it had a new trophy guide written and posted on the site too. (As of writing, it has generated 22,000+ views.)

A previous trophy guide for Heavenly Bodies on PlatGet estimated a 5-hour completion time with a 3/10 difficulty for the game. When I ran these numbers past developers Josh Tatangelo and Alexander Perrin, they were surprised at the suggested ease of the achievements. ‘If you’re talking about difficulty as a measurement of time involved, then when you stack it up against something that you’re going to need 200 hours of play, then sure, it’s probably a 3/10. But if you’re stacking it up against the amount of hair lost, then I wouldn’t be calling it a 3/10,’ Perrin told me, laughing.

‘There are people who write us angry emails and letters just being like, this [game] is too hard. With actual anger.’

As with the Samurai Punk games mentioned earlier, it’s trophy guides that offer a quick overview of the game’s achievement requirements, and suggest short and uncomplicated completion times that allow players to discover and play many smaller games that they may not otherwise.

In this drive to slice through a game in the fastest way possible, Tatangelo finds a parallel between the practices of achievement hunting and speedrunning. When I mention an exploit that I stumbled across in the trophy forums that makes it significantly easier to get one of Heavenly Bodies’ achievements, he points to how, in the game’s budding speedrunning community, these exploits are referred to as ‘skips’. What classifies as a skip is heavily dependent on the game, but they regularly refer to unintended shortcuts that allow players to circumvent specific areas or challenges, saving them large amounts of time and labour.

‘We’ve had a few brought to our attention, but I personally like it when people find this stuff. I like that they find the semi-exploits, because it’s not like they aced the game with this one move,’ Josh says. ‘Unless it’s completely ruining someone’s experience, I’m happy for them to share that.’

Compared to achievement hunting, speedrunning may occupy a higher rung in a hypothetical ladder of respectability in gaming communities, but both contexts are connected by this shared drive to find the most optimal path through a given game. These popular metagaming practices showcase intensely focused ways of playing that leaves little time for any of a game’s ancillary elements.

Against Completionism

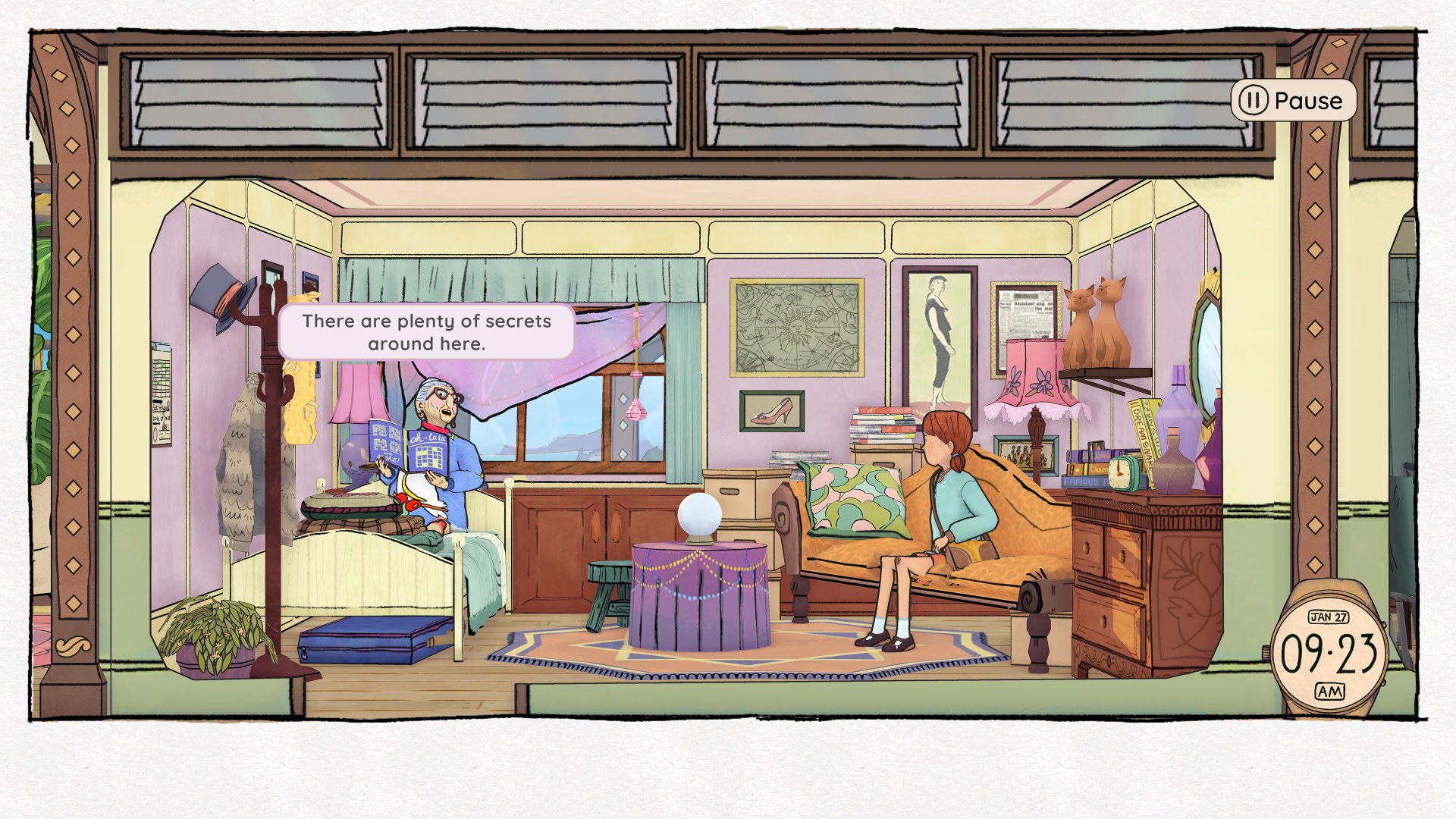

Wayward Strand, the real-time narrative adventure game set upon an airborne hospital in 70s coastal Victoria, approaches achievements in an entirely different way to the games outlined above. Speaking to Ghost Pattern developers Georgia Symons and Jason Bakker helped explicate how the game challenges traditional trophy conceptions, and the tension between conventional achievement lists, and the studio’s design ethos.

For starters, Wayward Strand’s achievements aren’t directly tied to linear or temporal progression. Because the game’s narrative takes place over an explicitly demarcated three-day period, one can see the way that these clear markers could be exploited for easy achievements.

‘We knew that we could easily tick off a few achievements by doing ‘day one’, ‘day two’, ‘day three’, but we also knew that it was a really hollow and cynical approach to our particular game, because of the real time mechanic,’ Symons says. ‘Unless you literally stop playing the game, you can’t not get to day two. It’s literally not an achievement.’

Because of this, there was an internal hesitancy with the game’s achievements. The demand from major platforms to include achievements in all published games seemed to butt up against the philosophy of Wayward Strand. ‘We knew immediately that we were going to have to be really careful, because even though achievements sit a little bit outside the game, it would, in the view of most of the team, actually destroy the game to have people be incentivised to care for these characters,’ Georgia says. ‘The entire premise of the game is that spending time is its own reward.’

Playfulness, then, was key – Wayward Strand asks you to play with a curious mind, and this is reflected in the achievements. Your traditional trophy hunter may be stopped in their tracks by the game’s ambiguous achievement descriptions, which read as poetic rather than instructive. Unlike achievements in most games, which nudge you towards, if not tell you outright, what is required to complete them, Wayward Strand’s are lyrical and mysterious. The description for the achievement ‘Teenage Ghoul’, for example, simply reads: ‘So spooky.’

Challenge was still considered. Without creating an ‘excellence mindset’, the devs still put achievements in hard-to-reach places. ‘A lot of achievements you only get if you do the task as wrong as possible, or if you completely don’t hear about a given story thread,’ Symons tells me. It was designed like this that still allowed for a degree of difficulty, without letting players think they’ve ‘been the best at caring for people, or being on work experience, or helping their mum’.

Bakker echoes this sentiment: ‘Our design philosophies for the game are like, we’re okay with being abrasive to players, or doing something that they’re not going to expect, and I think we extended that to our achievement design: to be like, let’s not do what a player might expect here. Let’s go off in a different direction and do something that is hopefully more surprising or interesting, as opposed to what they might expect.’

Maintaining the game’s vibe meant consistency between its internal and external parts. ‘We wanted to make sure that the voice of the achievements was in the voice of the game,’ Symons says, elaborating on a specific moment where this synergy was important, used to extend and emphasise a significant narrative experience.

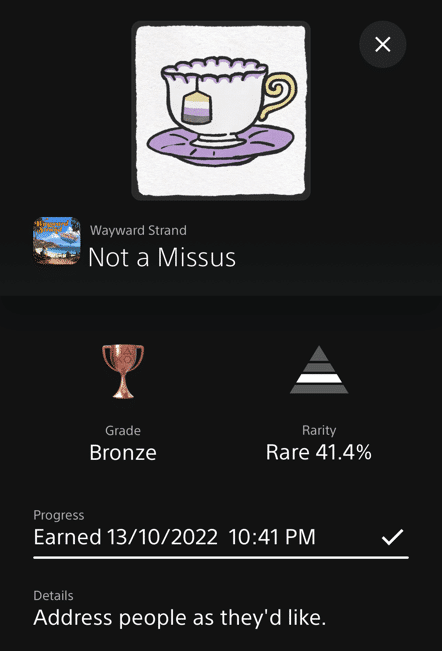

For example, Esther is one of the many elderly residents of Wayward Strand’s hospital airbase you’re able to speak with in your playthrough. In interactions, however, they’re uncomfortable with you referring to them as ‘missus’ – ‘I’m done with being a missus,’ they tell you. ‘Never got much out of it, anyway.’

When they abruptly confess this to you, an achievement pops up: ‘Not a Missus’, paired with the description, ‘Address people as they’d like.’

‘We came to a decision that Esther is someone who has an experience of gender where they don’t feel comfortable as a woman, but everyone kind of sees them as a woman,’ Georgia says. ‘In our dev team as much as possible, we used they/them pronouns for Esther, but we were also aware that in the 1970s, that language wasn’t widely available, so all of the characters use she/her pronouns for Esther.’

It became a sticking point for the devs, a feeling of erasure stemming from the game’s realistic grounding in the milieu of 70s Australiana. ‘When you have this achievement pop up being like “Not a Missus”, it reinforces the impact of that. It makes you go, “Oh, that is actually a story beat – that’s not just this idiosyncratic person being idiosyncratic, this is something that’s true to them.”‘

In Wayward Strand, achievements become more than a checklist, and are imbued with renewed significance. They become, as Georgia says, an extension of the game’s narrative, and in this specific instance, an underscoring of importance that’s able to acknowledge the social realities of two time periods at once.

This article was commissioned by GamesHub and Creative Victoria as part of Wordplay, a games writing mentorship program held during Melbourne International Games Week 2022. Read more from the cohort: