Surrounded by chai lattes and the tinkering of teaspoons in a minimal-aesthetic café, I sat with Tim Dawson and Wren Brier, the creators of the hit game Unpacking, during Melbourne International Games Week 2022.

As a writer and researcher in the subject of home, I’m fascinated by how people engage with their home-places. By nature, I was immediately drawn to Unpacking. In this game, you come to know the main character simply by handling her possessions, and linking subtle fragments of narrative between stuff, places, and the people she lives with.

My own playthrough of the game confirmed my own beliefs about home; that it is fluid, reflective, a human need that is often overlooked until a game like this comes along. I was not prepared for how smoothly the mechanics play with more subtle notions surrounding the home.

In my conversation with Tim and Wren, we often came back to the acceptance of change, and how the illusion of control is so necessary for both gameplay and feelings of at-homeness.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

GamesHub: Do you have your own definitions of home? How much does it factor into your lives?

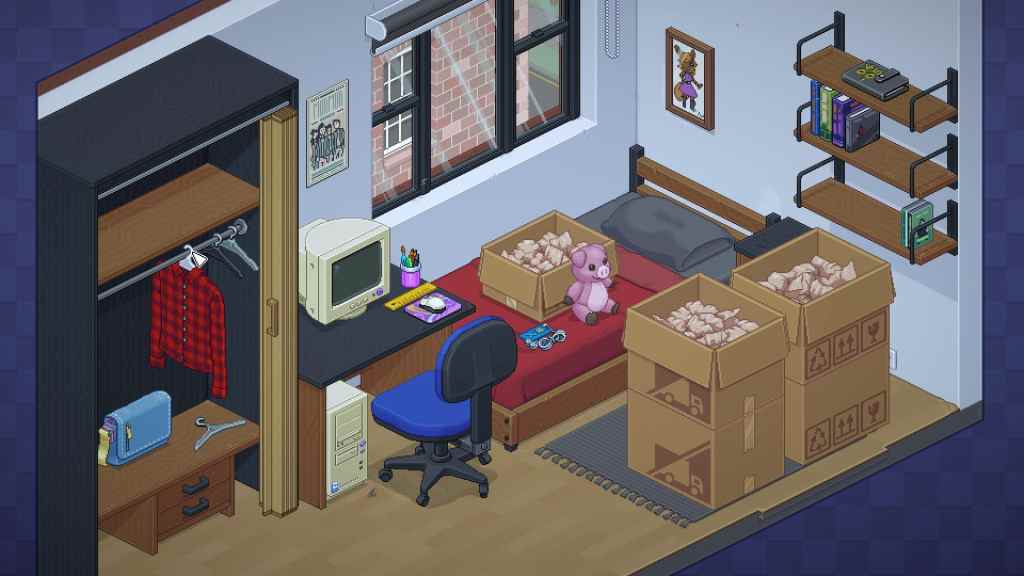

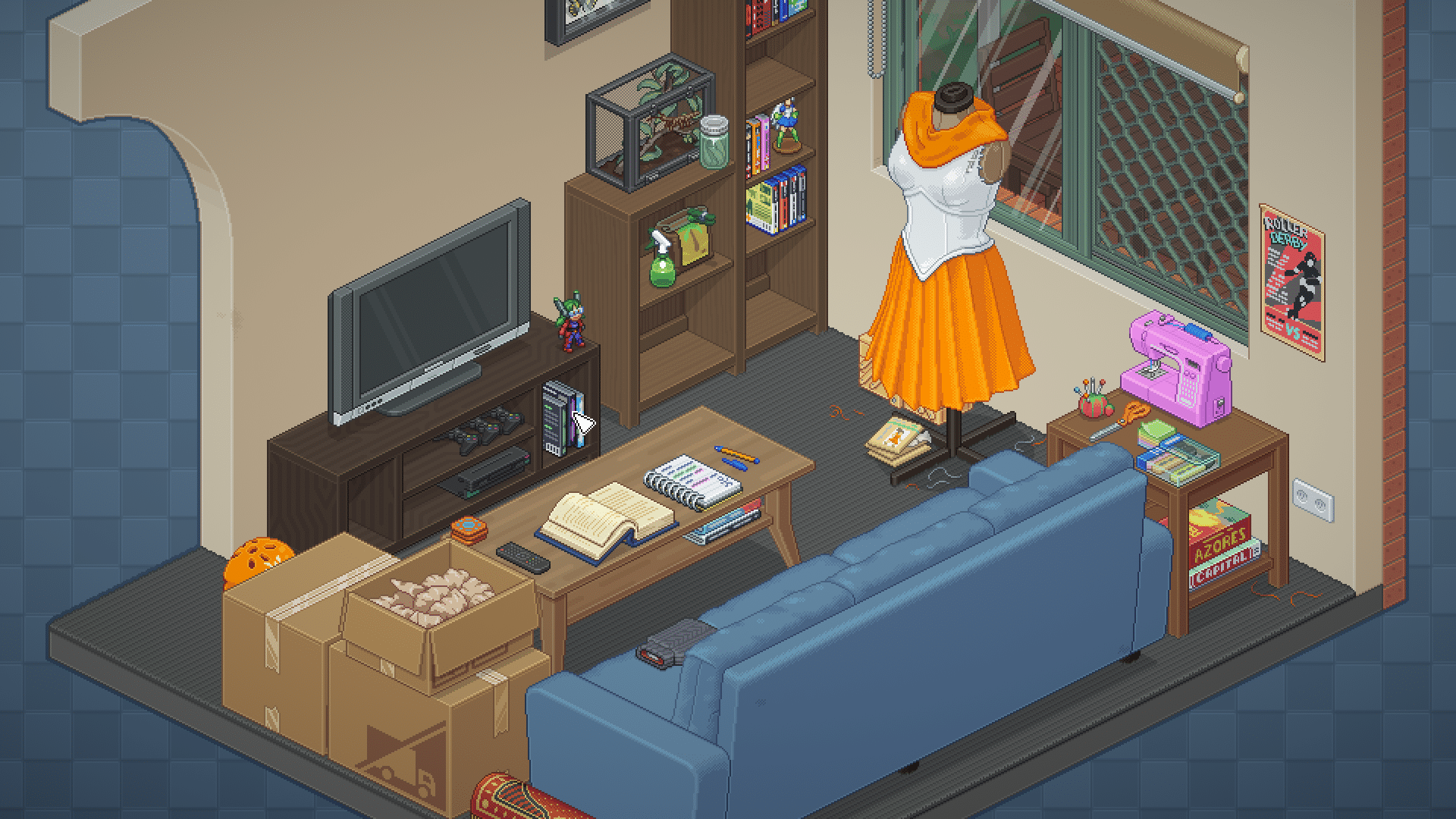

Wren Brier: Home is where your stuff is. You go to a place and it’s empty and doesn’t mean anything to you yet. It’s just four walls and a floor and a roof. But once you fill it with your things, it’s suddenly yours.

It’s also about where I can feel at-ease, like no one is watching me and I can rest. It’s where your stuff is, because it’s the things you’ve collected over time that mean something to you, that are useful to you, that represent you. And once you have a place that’s full of those, that’s a place where you can feel comfortable.

Tim Dawson: It’s the same with moving. There’s something strange about decorating a place with all your stuff, right? Especially if you’re moving long distances, you get there before your stuff and it’s more like you’re just camping there. Eventually your stuff shows up, and then it feels comfortable again.

How do you feel about the way Marie Kondo deals with ‘stuff’?

Wren: I find it really helpful because it’s a method that recognises that items are meaningful but at the same time, they can really complicate our lives and clutter them – and make us less happy too. I like how she personifies items. Does this item spark joy? If not, you go thank you for all the good times, all the things it helped you with, and then you’re ready to let it go.

I think that’s lovely, because that’s something that I have struggled with. Getting rid of items can feel kind of brutal and sad, and instead you’re saying this is just a goodbye.

Tim: When we started working on the game, everyone kept bringing up Marie Kondo constantly, and it was slightly uncomfortable because in some ways Unpacking is a game that celebrates stuff, while Marie Kondo is advocating for having less stuff.

But I realised as we were working on the game that due to the nature of not being able to have 10,000 items per level, we were actually leaning into that kind of curated item list.

That was partly based on the move that inspired the game, because I was moving from an apartment that I’d been living in for five years and Wren made me correctly identified that, due to space limitations, I should be selective about what I put into the boxes. That was why, when we were unpacking, it felt a lot more dynamic, because everything coming out was a beloved item. We ended up hitting a bit closer to that philosophy than we intended, because we didn’t want to waste moments with items that didn’t mean as much. It’s different for games because we’re sparking joy in a gameplay sense.

Wren: And then you spark joy for our character. As the player, your agency is very limited to specific situations, so you don’t get to choose what items the character owns. You get the items that the character brought with her, and you don’t even know what they’re going to be, and this is where your agency comes in: you have control over the space that the character lives in.

The idea of control is a theme that came through the game subconsciously. What you can control in your life and what you can’t, and learning to be okay with the things that you can’t, and learning to accept them. As we were working on it, I realised to what extent this reflects my life philosophy.

I had been made redundant a couple of months before moving, and I was just taking a little break and this [the game] is just something that happened. As we started developing the game full-time, the next month, I got diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. You get dealt certain cards you don’t expect, and they can throw a spanner in the works, but then you can decide what you’re gonna do with that. You have to move forward with those cards. You play Unpacking, you get a room, you get a bunch of items, and you go, what do I do with these?

A lot of the milestones in your game are tied to romantic relationships. How does it feel to have the origin of this game so entwined with your personal, romantic life?

Tim: There’s definitely that weirdness of it being inspired by a real-life move, and then we’re also living, working, and dating. We’ve had this amazing journey with the game, but it’s definitely intense. I’m conscious of tying our relationship together to the game – that feels like a risk, right? It feels like putting all eggs into one basket. I was aware of that, but I’m glad we’ve come through this alright.

As for Wren, I love collaboration. Witch Beam was a studio I started with two other people, and it was in the right place to make Unpacking happen the way it did, but so much of it draws on Wren’s instinct for story.

Wren: I want Tim to get more credit for the game. Tim is the glue that held the entire game together. He programmed the entire thing. He also supported me emotionally through it, and very much enabled me. I mentioned in my keynote at GCAP I’d had some experiences that really hurt my confidence with friends and with workplaces, where I was not trusted and nurtured to do a good job. And working with Tim was the opposite of that.

Is there a way that someone can play Unpacking wrong? Or have you seen anybody take something away from it that doesn’t gel with your personal philosophy?

Tim: The way that feels the most wrong to play the game is to not think about it. If you engage with the mechanics on the simplest level, which is like, four items need to be placed somewhere where you won’t get a red outline, it feels very much like you’re swallowing without chewing. I would hesitate to say that’s wrong, but that’s definitely the least interesting way to play the game.

Wren: I had a feeling that you (Tim) would say that, because we do get some players that tell us that the game is too short, and they played it in two and a half hours. I actually don’t understand how you played it in two and a half hours because it takes me, the developer, three hours. I’m just like, did you even notice the story?

Tim: More than some other games, it’s a collaborative game in that it’s a bit of a mirror. Items are going to mean more if you relate them to what you think they might mean, based on your experiences. You need that point of reflection, you need that time to think about it, otherwise you’re not gonna get as much out of it. It’s a little bit like playing through a game with the sound turned off.

Wren: It’s a very low-friction game, and friction is usually what slows you down in games. It’s low friction on purpose because we want people to find their own meaning in it, and generate the friction themselves. We find players give themselves more rules than we actually give them. The friction is the noticing-things and thinking-about-things. But in terms of mechanical friction, there’s none, so you can go through the game really fast.

Do you think you can tell much of a person or their current state-of-mind by how they play game?

Tim: One of the exciting things we noticed in some of the earliest public tests is that we thought people were going to unpack and put things where we expected them to. We were really surprised that people’s kitchens looked all different to each other, even though it was just plates and cups and a microwave. Everyone had their own kitchen, and would finish playing and take a photo of their kitchen.

Wren: The really insightful bit was when couples would play, and they would learn a lot about each other through playing the game, especially if they didn’t live together yet. They would be like that’s where you put this?!

Tim: We suddenly got this insight that this game is going to be more provocative than we thought it was. It’s going to make people think more about their relationship with their own living space.

Wren: Another interesting thing was when we showed the game to the general public for the first time, it was on this high-up screen so everyone in the line could see what the person at the front was doing. We were worried that people would be like I‘ve seen it being played multiple times, why would I want to play it now? But instead they saw how other people were unpacking, and thought it was wrong. They were itching to do it correctly.

Initially, when we first implemented the game’s validation system, we made it a lot more strict because we zoned each item to where we thought it should go for us, personally. It made players real mad, because they wanted to put things where they thought was right, and we said okay, let’s change this so it’s more lenient, and people can make their own rules within our rules.

We gave people more choice, and more options for where they wanted to put stuff, but we didn’t let them do absolute chaos, because then it ruins the point of the game. This is not a game about making shenanigans, it’s a game about unpacking a home, and making it feel nice.

Do you think there is a certain mood you have to be in to play the game, or does it hit you differently at certain times of life?

Wren: The interesting thing I found was people coming at it from angles we didn’t expect. We’ve had people play it after a breakup, and really connect with certain elements of the game that had to do with relationships.

We’ve had someone play it who has a daughter about to start university, so he looked at it less like I am playing this character, and more like I am helping my daughter pack her things in the childhood room, and then unpack them in her university dorm. It was very interesting to hear a different perspective on the game like that.

One more question: Is there a lore behind the little chick plushies in the game?

W: Okay, so the lore behind the little chick plushies in the game is: I thought, what if I design a series of items that we could one day make plushies of and I could own them? But the other thing is that I’m a collector, and I figured our main character should collect things.

I thought, what if she collected a set of toys and new ones keep coming out? And so, every time she gets the latest ones, she grows her collection. I thought it would be fun to see over the course of her life.

This article was commissioned by GamesHub and Creative Victoria as part of Wordplay, a games writing mentorship program held during Melbourne International Games Week 2022. Read more from the cohort: