Video games have become a rich site for exploring coming-of-age themes – If Found…, Night in the Woods, and Life is Strange, to name a few. In Wayward Strand, studio Ghost Pattern adds its unique interpretation to the growing body of games that deal with teen and young adult perspectives.

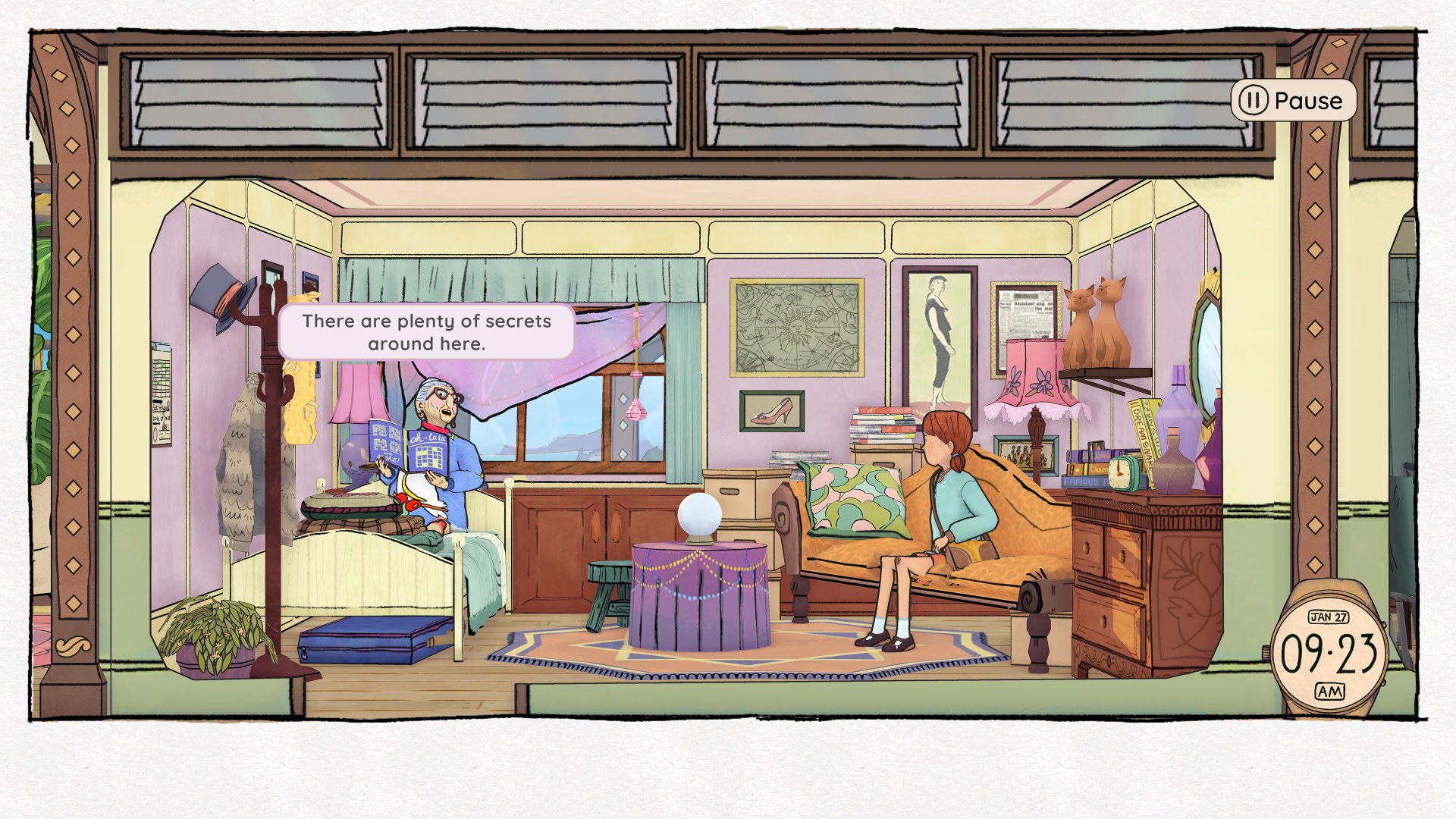

Wayward Strand is set in Australia in the summer of 1978, with players taking on the role of Casey, a 14-year-old girl who accompanies her mother to work on an airship hospital. Casey is an aspiring journalist, so she takes the opportunity to learn more about the hospital and its patients for a school newspaper article.

Read: Wayward Strand review – The clock keeps ticking

Ghost Pattern recently shared a demo of the game on Steam, which gave us a brief window into the airship and Casey’s investigation. It also delivered some insight into how the studio went about weaving coming-of-age themes into the playful mechanics of their adventure game.

It starts with a curious 14-year-old

Spending the school holidays at a parent’s workplace will be a relatable experience for many, and Wayward Strand seems to capture that uncomfortable presence so well. Casey is unsure how to pass the time – there’s a tongue-in-cheek option to ask the nurse, ‘can’t you just give me tasks to do?’

You’re free to wander anywhere on the airship, and there are no right or wrong areas to visit. At first, Casey will poke her head into the rooms of various patients and the voice acting beautifully conveys the timidness of a teen introducing themselves to a stranger.

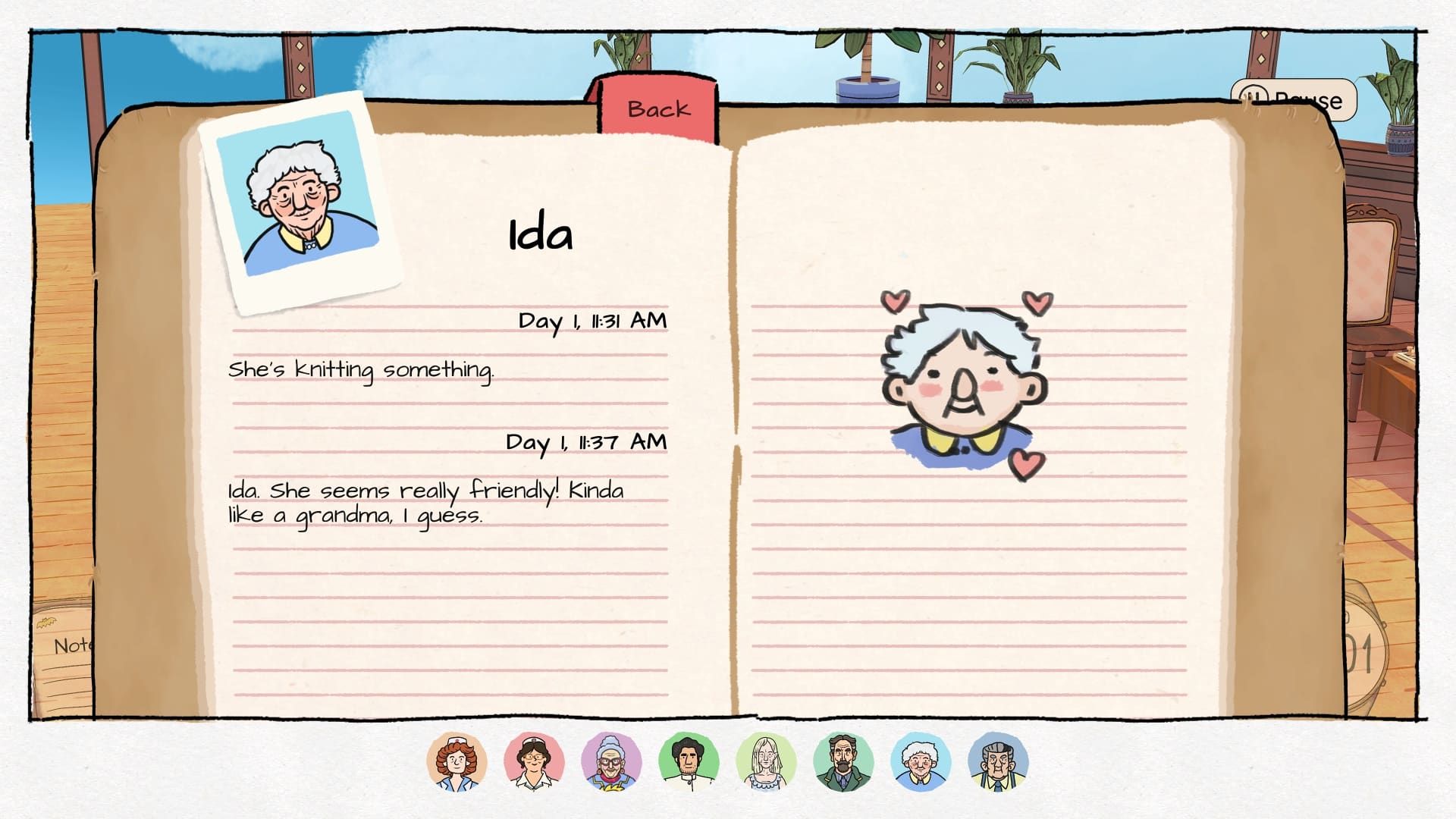

Casey, however, does establish a loose purpose: to research the airship hospital for her school newspaper. This involves talking to patients or eavesdropping on their conversations to learn more about their lives and the hospital itself.

Curiosity is a major driver of adventure games, as many conventionally situate a player in an explorable space among interactable objects. Playing as an intrepid teen journalist, however, brings to mind the appeal of teen girl sleuths like Nancy Drew or Veronica Mars.

Following leads and taking notes allows these characters to take agency in making sense of the world around them. Casey’s sleuthing does not involve points to score or enemies to bring down. Rather, players piece together the investigation through listening and empathy.

Wayward Strand’s narrative style is multi-linear, meaning that several stories play out at once in real-time, regardless of whether the player is present to interact with them.

This is a humbling storytelling strategy. It decentres the protagonist from being the hero of the story by reminding us that life goes on around us.

Learning about the lives of the patients can be read as informing Casey’s coming of age, as her worldview is enriched through their stories. At the same time, setting a coming-of-age game in an aged-care ward invites a powerful reconsideration of growth and transition.

Ongoing growth

When we think of the coming-of-age genre, we think of the identity and social trials faced by teens and young adults as they transition into adulthood. Yet growth and transition is an ongoing component in all stages of life. When the famous philosopher Simone de Beauvoir published a pivotal study on the elderly, the English title of her book was ‘The Coming of Age.’

Interestingly, that study was published in 1970, the same decade as Wayward Strand’s setting. It aimed to draw attention to forms of public ambivalence towards the elderly. Beauvoir noted that the aged were socially devalued because they no longer contributed to the capitalist workforce; a perception that sadly remains relevant today.

Wayward Strand dispels these perceptions by offering a cast of elderly characters with complex inner lives. The team at Ghost Pattern draw on their own personal experiences, and have undertaken extensive research and consultation to tell these stories with care and nuance.

The patients are not the butt of the joke – they do not personify the cranky grouch or wise mentor stereotypes. They are permitted to be multidimensional with their own human perspectives. Some will be happy to chat with Casey, while others will request space.

Critical insights begin to surface through the game’s choice to place its young girl protagonist within an aged-care ward. Like the patients, Casey shares an existence outside of the productive workforce, and so she similarly occupies an uncertain social status and unsettled sense of purpose. Perhaps this is why Casey and the patients become drawn to one another.

Wayward Strand detaches itself from idyllic notions of productivity. It’s a game that instead celebrates being, and the connections that are forged in the process. It communicates this through its absence of goals, rewards, and win or lose conditions.

The game offers an astute interpretation of the coming-of-age genre, which centres on self-discovery but, more crucially, is about accepting the process over a mythical end goal. The more nuanced coming-of-age stories are the ones that reject a fixed ‘overcoming’ of adolescence and instead recognise that identities remain in flux.

Intertwining Casey’s story with the ongoing development and intricate lives of the game’s ageing characters works to dissolve our preconceptions of linear, productive, and youth-oriented notions of growth. Re-examining growth in this way draws attention to the experiences of those that occupy the margins of productive labour.

From that early interaction with the nurse, Wayward Strand immediately sets up the notion that games do not need to be made up of ‘tasks to do’ in order to construct a rewarding experience.

The absence of productive play communicates an all-the-more powerful message in a game about growing up and growing old: Wayward Strand reminds us to value ongoing transformation through empathy, care and connection.

Wayward Strand will be released on 15 September 2022 for PC, Nintendo Switch, and PlayStation 4.