“The goal of funding was that I, and everybody that was working on [Spiritwell], could spend more time doing what we love doing best – which is just making games and being able to just be creative, and do creative things,” said David Chen, lead developer on upcoming whimsical adventure game Spiritwell.

“There’s a lot of talent and good work coming out of Australia that I think deserves to be supported, and has a lot of potential for the future, and the way stories are told, and the way people enjoy media. Games are becoming very central to that.”

Chen is one of many Australian game developers who recently benefitted from new game funding initiatives established by Screen Australia, in an effort to support and promote smaller, locally-made creative projects in development across the country.

As the local industry begins to shed stereotypes – with around 81% of Australians reportedly now playing video games – the value of the artform is becoming more understood. Video games aren’t just fun ways to spend time. They operate as cultural transmissions. They share very human stories – whether specifically about Australian culture, or as influenced by the values and experiences of developers.

Commercial outcomes

Practically, game funding benefits the economy, with Australians purchasing around AU $4.21 billion worth of video games in 2022 alone. Australian-made games contribute to this total, and equally, they represent a valuable export – with recent releases like Unpacking and Cult of the Lamb achieving success in the global market, as high-profile, locally-made video games that demonstrate the country’s cumulative talent.

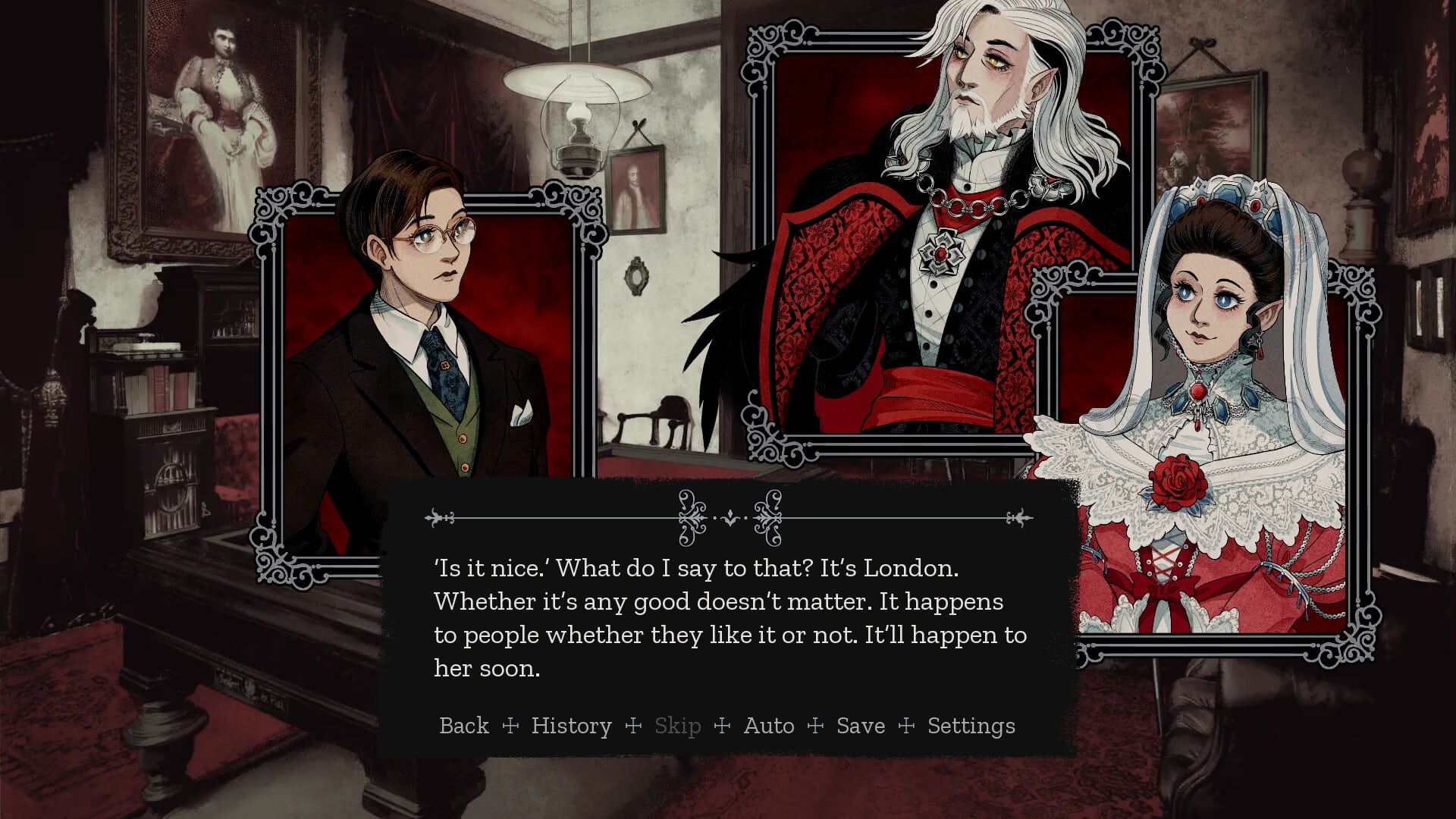

“Being able to rely on state funding is really valuable, especially because a lot of Australian state funding has had positive commercial outcomes … there’s a good reason to trust and take a bet on a lot of people here,” says Mads Mackenzie, lead developer of upcoming romantic horror visual novel Drăculești.

For developer Simon Boxer (Ring of Pain, Winnie’s Hole), the core difference in funding games, and the reason why global governments should be paying attention, is simple. “Economically, the potential for rewards within this industry is much higher than many others because it’s not physically limited,” Boxer told GamesHub.

“We don’t sell our time, we sell an infinitely reproducible product. It makes sense to invest in games because even though it’s a very risky industry, if a studio breaks through (from a national perspective) it offsets the other losses and the overwhelming majority of income is generated overseas. It just makes sense for the government to fund a booming industry which also adds to culture.”

Read: 2023 NSW Budget guts game development support in the Australian State

States like Victoria and Queensland have championed video game development in recent years, supporting new creative works that have contributed significantly to economic success, creative fulfilment, and cultural transmission.

Initiatives from Screen Queensland and VicScreen provide strong support to developers on multiple levels – guidance, goals, and funds that allow projects to evolve, to become more ambitious, and to reflect the artistic intention of their creators.

A range of local developers speaking to GamesHub for this article described funding as absolutely essential to game creation – specifically, well-realised creation on a reasonable timeline, with proper resources, and backed by third-party support. Not only did recent funding from Screen Australia allow many teams speaking to GamesHub to expand their projects, but it also led to the creation of new jobs – yet another key metric for a well-functioning economy.

Expanding ambitions

“Since the Screen Australia funding was approved, one of the big things for us is that we’ve been able to actually gather much more of a team, so that it’s not like having to wear a million hats at once,” Mackenzie said. “[Without funding] it probably takes us five years or longer. [It’s] also that relief of, ‘oh my god, I don’t have to do everything myself. And we can get this done in a reasonable timeframe.'”

For Boxer, funding has allowed his various projects to expand in scope, and he’s been able to invite programmers and artists to contribute their talents while being reasonably paid.

“Without that initial funding I don’t think [Ring of Pain] would’ve reached the level of polish (and lack of bugs) to successfully exhibit,” said Boxer. “I still couldn’t pay myself, but it was enough to get some audio in and programming help … Most recently, Screen Australia funded another project I’m involved in called The Dungeon Experience. That’s been pivotal to us hiring a programmer and artist, while enabling us to self-publish the game since Jacob Janerka (the studio co-founder) doubles as some sort of magical internet whisperer with a track record of viral posts.”

“We probably would have had a budget to keep ourselves going,” Janerka said. “But with the budget from Screen Australia and VicScreen, it really gave us the capacity to bring this project to a new level of polish – and just be able to do things that we wouldn’t have been able to do.”

Little Pink Clouds, the Melbourne and Tasmania-based studio working on the cosy adventure game Letters to Aralla, comprises a group of friends who banded together after graduating from university at RMIT, with the hope of using their skills to work on creative, fulfilling projects. Gaining funding from Screen Australia and VicScreen allowed the team to expand, and to gain some measure of stability in the years following coronavirus lockdowns.

“To make a single game is such a complicated art form,” Chantel Eagle, director and lead 3D artist at Little Pink Clouds said. “Games are basically art – but it’s so complex, and all of the things you need to account for, all these different fields, need to merge together to create this one interactive art piece.”

Read: Screen Australia announces $3 million support for selection of local games

“That’s a culmination of everyone’s different talents that go across UI design, character design, 3D art, sound, design, music. All of this needs to come together, and funding allows you to cover these fields … You need to be able to bring in people that are better than what you can do. I can’t do music, and it’s going to take years for me to try to train myself to learn the skills. Or I could bring someone who’s far better at it, and bring them along for the ride to create this project together, in this really beautiful collaborative process.”

Yet games funding isn’t purely about money and jobs, as it’s often reduced to in professional terms – it’s about creativity, and art, and how it can impact audiences. For many developers, it’s also a validation of their ideas and talents.

Pursuing dreams

“I think [games funding] just allows anyone in general to pursue their dream,” Eagle said. “Since I was a child, [my dream] was to create these interactive worlds that you could explore and run around in, and really feel immersed in. In order to achieve that, you need funding.”

On a personal level, game funding is also a confidence booster.

“As a creative, it’s hard to believe that what you’re working on, what you’re making, actually has value,” Chen said. “I would love the world to just enjoy [Spiritwell] – but it’s also nice to get validation, in the development process … knowing there’s that level of belief is something that I’ve struggled with a lot, either having belief in myself or wanting people to believe in me. That’s a really big thing, for me.”

Other developers speaking to GamesHub shared a similar sentiment – that while funding, in theory, was based purely on monetary aid, its consequences were far-reaching, for confidence, support, and building a sense of community within the Australian games industry.

“It’s definitely a relief,” Mickey Krekelberg, developer on Letters to Arralla said. “It’s good to know that somebody believes in you, and believes in your creative vision. Because you do spend a lot of time in your own head, and there’s a lot of doubts in the creative process. So having those external people come in and say, ‘yeah, we believe in it, too’ is really gratifying.”

“You’re providing people with voices when they wouldn’t normally have one,” Jacob Janerka said. “It’s a good feeling to be able to receive these grants and know that there’s someone on your side that believes in you. For a lot of people … that can be a huge boost to confidence.”

In many cases, games funding also allows stranger creative works to blossom, expanding the Australian arts scene in compelling new ways.

In describing the recent titles funded by Screen Australia, Mackenzie related the eclectic array to Australian New Wave cinema – a movement in the 1970s and 1980s that saw countless filmmakers exploring Australian culture in cutting-edge style, via genre films, and experimentation in the medium.

By taking a chance on stranger projects – like The Dungeon Experience, which is an absurdist fantasy comedy, and Drăculești, a horror-romance work inspired by Dracula – Screen Australia is enabling the growth of modern Australian art. And like Australian New Wave cinema, these creative works have the potential to elevate Australia on a global cultural stage.

Building momentum

In recent years, various funding bodies have stepped up to support the Australian games industry, forging new initiatives as game development in the country becomes more accessible, economically viable, and mainstream. VicScreen, Screen Australia, Screen Queensland, and Screenwest are leading the charge, with state-based funds across the country aiding new creative works.

But despite the Australian Government, as a whole, strengthening its commitment to the arts with incentives like the Digital Games Tax Offset and a variety of smaller funds for eligible teams, it’s clear more work needs to be done – particularly as certain states like New South Wales flag behind.

As recently announced, around AUD $188 million of the state’s budget was recently cut from screen and innovation programs in NSW, including several that benefit the games industry. Tax rebates in some areas have also been paused, and video game-adjacent projects like the rebuilding of the Powerhouse Museum in Ultimo have been rescoped.

“Other states across Australia are increasing and improving their game development funding to reap the benefits that a thriving, supported and recognised game development sector can tribute to a creative and technically skilled local economy,” advocacy body IGEA said of the changes. “Sadly, NSW is now headed in the opposite direction.”

Should the positive momentum of games funding in Australia continue, it will need to thrive with the full support of every state, so that local developers can grow together, pushing Australia towards a brighter creative future.

“Having this government support means that there are indie creators who wouldn’t have opportunities to either get work or pursue their creative passions, and can now do that – and support each other,” Mickey Krekelberg said. “Otherwise, it just wouldn’t happen. It just wouldn’t exist – and the creative community would fall apart.”

“If these sorts of government bodies weren’t there, imagine all of the games that you know they’ve funded so far,” Chanel Eagle said. “None of them would exist. That’d be like hundreds of games over the years that these have existed that would never happen … and we know that these games that are funded by VicScreen and Screen Australia are majorly successful … If those didn’t exist, we can imagine a very different future.”

As Eagle says, a future without video games, and without the creative voices of Australia’s talented local developers, is no future at all.