In 2023, the worst thing a game can do is waste my time. Did I really spend an entire weekend trying to bridle a unicorn in King’s Quest 4? Perhaps my memory and attention span is unravelling, as a result of too many adult responsibilities, and the absence of sufficient time to play games.

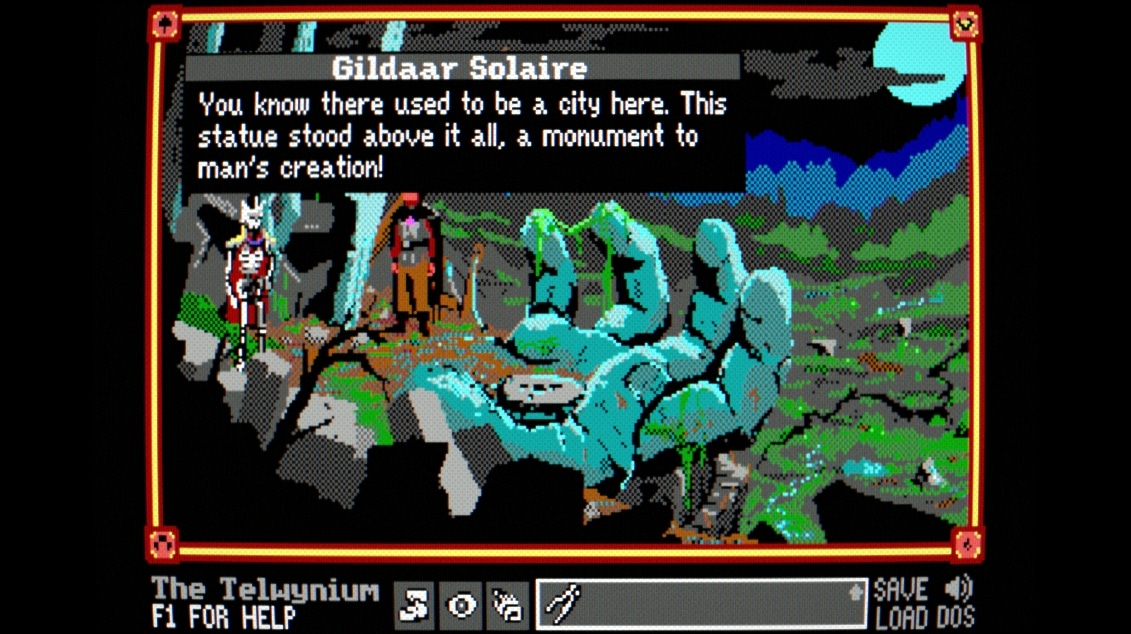

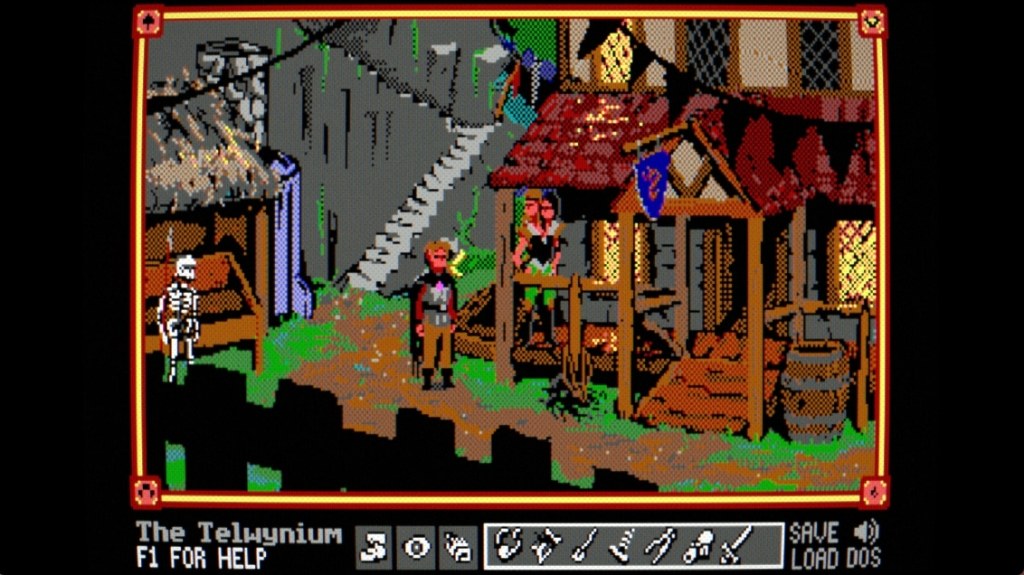

Modern point-and-click adventures rarely disappoint, in that regard. Even the most retro-styled (with the possible exception of Stair Quest) deliver puzzle-solving smugness, and a gripping story, fast. Having recently savoured The Telwynium, Books 1 and 2, I became interested in asking developer, Dave Lloyd of Powerfoof (Crawl), how he created such a cleverly concentrated, nostalgic treat. His answers speak to careful planning and practised skill, as well as revealing a wealth of clever design ideas.

Chapters:

Read: Behind the high-risk development of The Forgotten City

Be extra specific

The Telwynium games are small, at approximately an hour each, and unfold over only a handful of scenes. A grand sense of scale develops, nonetheless. While you’re engaged in seemingly menial tasks, like finding wood for the fire, your companions discuss the violent destruction of their village, the magic of birth, even a rich, but lost, civilisation. Lloyd says, ‘Alluding to history is a great way to flesh out the world.’

He provides an example: ‘When you look at a beehive, Pendar reminisces about a swarm of hornets that once chased his friend, Witt, “halfway to Springbank”. I don’t mention Springbank again, but mentioning “Springbank”, specifically, provides a solid sense of place, and adds of history and depth to the characters.’

This made me laugh, because Springbank may be a throwaway location, rather than realised on a map on a design document somewhere, but it’s firmly on the map in my head, as he intended. Lloyd says, ‘I’ve always found that being very specific about small, unimportant details is what makes a world feel real, and bigger than what’s in the game.’

I also particularly love Lloyd’s choice of language and the blurred line between obscure, historical terminology, like aumbry and porringer, and made-up words, like ‘aichem’ and ‘aldor’. Context fosters an immersive kind of understanding, and the world becomes both familiar and peculiar, at the same time.

The humble vividness of incidental details, like dinner in the tavern; honeyed chestnuts, stewed lamb, string beans and garlic mash, reminds me of rushing to the katta’s inns, each night, in the Quest for Glory series, to see what was on the menu. Noting the smell of a bleached skeleton in the sun is a less pleasant, but no less compelling, example of such nuanced storytelling, too.

The Telwynium has an abundance of curveballs

These concise, story-crammed Books are so satisfying that I’m desperate for more, which comes as a result of ingenious narrative twists and cliffhangers. Lloyd says, ‘The best thing a game can do is surprise me.’

Book 1 posits that people aren’t always as they first seem. Alongside more classic twists, like being betrayed by a trusted friend, an entire race of (also possibly throwaway, but fascinating) humanoids is revealed with the lifting of a hood. I initially thought Book 1’s conclusion had come out of left field, but then realised everything I’d learned about magic and birth was being referenced.

In Book 2, hints about identity infuse the story. At one point, I believed I had figured out secrets about resurrection and bloodlines, then I knew I was wrong, only moments before the truth was revealed. Lloyd says, ‘People find it most enjoyable when they predict a twist just as it’s about to happen.’ And, of course, the cliffhanger ending in Book 2 was another unexpected, but entirely coherent, gut punch.

The Telwynium series is being created with Lloyd’s Unity tool, PowerQuest. Having used this myself, I can appreciate the complexity of the logic that is driving cutscenes and dynamic changes. Twists are less easily anticipated when delivered, for example, as you re-enter the tavern, having collected a seemingly unrelated item, rather than at the end of a structural section. This firmly reminds me of the Laura Bow games, specifically, the sudden appearance of a murdered corpse.

Lloyd is also channelling Game of Thrones, in that the safety of important characters is never assured. Lloyd says, ‘My initial idea for Book 1 was to begin by subverting the classic hero’s journey plot. What if Gandalf was murdered on Frodo’s first night away from the Shire?’

The Telwynium features commonplace solutions

‘It’s possible my dad read Lord of the Rings to me at an inappropriately young age, but I recall being terrified of something happening to Gandalf. My dad would say, “Don’t worry, there are enough clues here to assure he’ll be alright.”‘

Lloyd uses foreshadowing as part of storytelling, but also as a related kind of ‘Chekov’s Gun’ idea to flesh out puzzling. In this case, I didn’t need a rifle, but a different object, hanging on the wall. I’d previously examined and interacted with it, believing it to be simply another of the game’s decorative flourishes, until its true purpose suddenly became clear in my head.

I’ve solved a great many adventure game puzzles, but it’s rare I enjoy them this much. Another thing I love is that (with the exception of a few magical items), everything in The Telwynium is mundane; coal, wood, clay, reeds, fishing hooks, improvised pieces of cloth. Lloyd says, ‘I always wonder how I would solve this if I were the character, and if there’s a mundane solution that works, then hopefully that’ll click for players, too.’

‘For a story-heavy game, the most important consideration is that the puzzles feel in-character. Puzzles are in-line with the character’s goals. They make the world feel interactive and therefore more immersive, giving the player agency, which is one of the great strengths of adventure games as a storytelling medium.’

Lloyd has been working (almost solo, but with a composer) on Telwynium during game jams, alongside a larger adventure game project, The Drifter. There are two more Books planned. He also promises, ‘There’s more to the (antagonist) Shadowfell than meets the eye. Their history, what exactly they are, their culture and belief system might be explored soon.’ Indeed, so far, the story of Pendar and his companions has been prominent, so I’m intrigued by this.

You can trust The Telwynium to respect your most precious adult resource; time, even as it transports you to a childhood era of Sierra’s SCI aesthetic. The experience is exemplary, especially given the Books are ‘choose your own price’, and a must for people interested in storytelling and puzzle design.

Lloyd is an expert in his craft. Don’t go halfway to Springbank to learn how to create a great adventure game, just play Telwynium and appreciate this in practice.

Originally published on: