If I described a game that had you explore the maze-like hallways of a spooky old mansion, with character-relative tank controls confining your movement abilities to rotating on the spot and walking either forwards or backwards, solving arcane puzzles to progress, and scrounging for scraps of ammo and health to fend off monsters in lumbering pursuit, you’d be forgiven for thinking I was talking about Resident Evil.

Yet four years before Capcom released the first Resident Evil game, French studio Infogrames debuted a game that met the above description precisely. Led by creative director Frédérick Raynal, in the very early 1990s, a tiny team in Lyon mixed Lovecraftian horror with a breakthrough merging of real-time 3D polygonal characters and 2D pre-rendered backgrounds to pioneer what would later be known as the survival horror genre.

Alone In The Dark was first released across Europe in September 1992 for DOS-compatible PCs. At the time, the video game world had never seen anything like it. Ironically, we almost didn’t see it at all.

Out of the Dark

Alone In The Dark was conceived in an idea Infogrames boss Bruno Bonnell had expressed to Raynal, of a game where the player explores a pitch-black environment. Resources to briefly light up their surroundings would be in limited supply, and so the player would come to rely on audio cues to get around. Bonnell even thought it should be called In The Dark.

With a few leaps of logic, you can see the circuitous path Raynal took from that simple high-concept idea to the final product. A game set almost entirely in darkness was perhaps impractical – certainly too high-concept for the time – but the core concept of the player feeling disorientated, and of having an incomplete picture of their surroundings, remained intact, albeit explored in a different way.

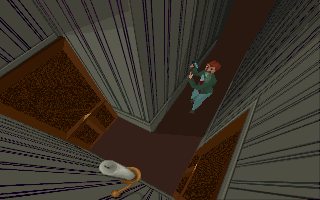

Raynal chose to present the action through camera angles fixed in unusual positions – high on the ceiling, or looking up from floor level, or even from outside a window looking in on the room the player is exploring. This break from a single perspective, consistent with the playable character, afforded Raynal and his team the ability to depict scenes with greater cinematic flair, heightening drama and tension through cuts between camera angles, and by positioning them to obscure the player’s view of what might be lurking around the next corner.

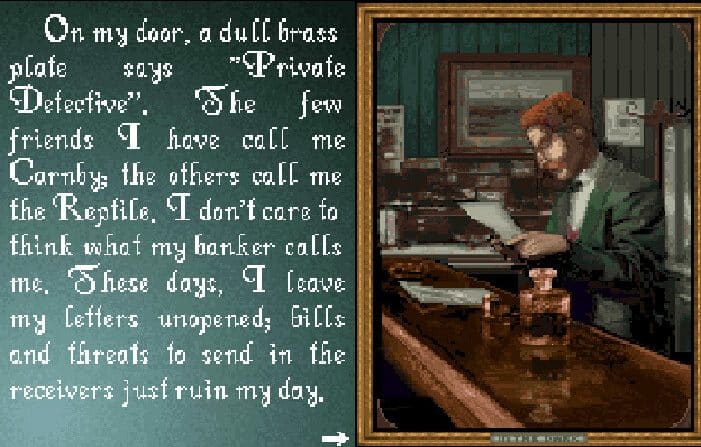

The bold and, for the time, revolutionary camerawork is on display from the game’s opening scene. Private detective Edward Carnby travels to Louisiana to investigate a decrepit mansion known as Derceto, home to the late Jeremy Hartwood, an author who hanged himself in the building’s loft. (You can also play as Hartwood’s niece, Emily, and the experience is otherwise identical. Carnby would take over as the series’ only protagonist in subsequent games, so I’ll refer to him as the main character here.)

As Carnby steps out of his car and enters the mansion grounds, the camera cuts to a shot from inside the top floor window, affording a view of the front garden. In the distance now, Carnby walks up the path to the front door below while, in the foreground, a pair of gnarled hands clutch the window frame, claw-like nails extending from emaciated fingers gripping the sill.

Inside, the door closes behind Carnby, causing him to turn in fright. He proceeds to walk through the mansion, heading for the loft, the camera switching every few seconds to present another new and skewed perspective on the warren of halls, ominously closed doors and corridors disappearing into darkness.

Dramatic string music keeps the anticipation at a brisk boil, while the only sound effects are the trepidatious tapping of Carnby’s shoes and the occasional creak wearily expelled by dusty old floorboards. It’s a tour of the mansion, essentially. A preview of the path you’ll be treading, albeit in reverse, once the game begins proper. It also serves as a small period of acclimatisation to the then-novel camera perspectives before you’re allowed to take the reins for yourself.

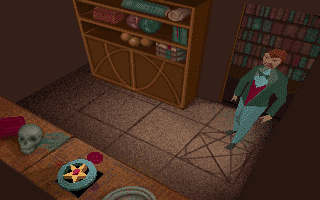

Playing Alone in the Dark, 30 years later

Playing Alone In The Dark today (it’s available on Steam and GOG) is slightly bewildering, even for someone who played the original when it came out. (In fact, one of my earliest professional reviews was of the original Alone In The Dark for the print publication Megazone sometime in 1993. The box still sits on my shelf.) The low resolution backdrops remain evocative; the chunky polygonal characters are still unsettling, though perhaps in a different and unintended way these days – the way details seem to writhe across bodies only enhances the grotesquerie, in my view. And those sudden shifts in perspective, those hand-picked camera angles chosen to deliberately obscure, are as nerve-wracking and discomforting as ever.

The controls are stubborn and painstakingly sluggish, as no doubt intended, in order to make you feel more vulnerable when an enemy bursts through a window in front of you. Yet even so, they’re clearly tuned too far in the wrong direction in that regard. Worse, Alone In The Dark really shows its age in the imprecise movement and pedantic requirements to position Carnby in just the right spot to interact with a particular object. Raynal and company were learning how to implement these ideas as they went along, and it’s in these finicky aspects that you can best see the prototype hasn’t been perfected.

Sadly, Raynal left Infogrames for rival studio Delphine Software after finishing Alone In The Dark, and he didn’t work on either of the two sequels that were quickly pushed out in the following years. (Raynal would instead go on to make the charming Little Big Adventure games, action-adventures that implemented similar technology to Alone In The Dark – they both saw real-time 3D characters charting a 2D pre-rendered space – but with a sharp tonal shift to the whimsical.)

Alone In The Dark 2 and 3 were hurried sequels built on the same engine. They expanded the scope of the series: 2 opted for a story involving pirates, and only touching on Lovecraftian deep sea mythos, while 3 further departed into the Wild West. Both games doubled down on action at the expense of atmosphere, and it seemed that for every step the sequels took away from that house in Louisiana, returns were severely diminished.

The darkness calls, again and again

Infogrames would twice attempt to bring back the series. In 2001, another French studio, Darkworks, was brought on for Alone In The Dark: The New Nightmare. Developed for the PlayStation 2 and ported to other consoles and PC, it was an effort to return the series to its roots, going back to the single mansion setting and emphasising puzzles and exploration, as much as shooting. Although not a failure, it suffered from comparison to the ascendant Resident Evil, which by this point was itself four iterations into its core series.

The second attempt was perhaps more interesting.

In 2008, a third French studio, the Atari-owned Eden Games, previously best known for driving sim V-Rally and Test Drive Unlimited, released a reboot of sorts, simply titled Alone In The Dark. Taking cues from immersive sims such as Deus Ex, this version sought to bridge the puzzle/combat divide by enabling players more freedom to improvise solutions using the game’s simulated physics and fire propagation systems. Brave, and more compelling in hindsight than it was given credit for at the time, Eden’s Alone In The Dark was nevertheless clunky and unrefined, a critical failure and a commercial flop.

Now, another Alone In The Dark is in development. Announced in August, published by THQ Nordic and developed by Swedish studio Pieces Interactive, the new game is once again simply titled Alone In The Dark. It promises to be a reimagining of the 1992 original where you’ll revisit Derceto as either Edward Carnby or Emily Hartwood. Details beyond that are scarce, though notably Mikael Hedberg, writer on several acclaimed recent horror games including Penumbra: Black Plague, Amnesia: The Dark Descent and Soma, is on board to write.

Making a new entry in the Alone In The Dark series cannot be easy.

Although it defined a genre, it was quickly surpassed by other more successful evolutions, most notably Resident Evil. Even with that series still well and truly alive in remakes and new entries, survival horror as a genre has never felt more diverse.

Resident Evil may still tower over its contemporaries like a nine-foot Eastern European lady, but it’s not the only game in town. If Pieces Interactive does draw inspiration from the likes of Amnesia and Soma, or even Phasmophobia, P.T. or Alien Isolation, to name three disparate horror games of the past near-decade, then maybe Alone In The Dark can finally re-emerge from the shadows.