‘We didn’t want to stand on Sid Meier’s lawn and set fire to everything,’ says William Dyce, the Australian bred, if not born, lead designer on Amplitude Studios’ Humankind, a grand historical 4X strategy game that seeks to explore, expand, exploit and exterminate the same territory as Sid Meier’s Civilization series.

Masked up in an open plan office space, Dyce is speaking via video call from Paris, the home of Amplitude, but a long way from Australia, the home he left to travel to the other side of the world – alone, at the age of 17 – to pursue a career in games development.

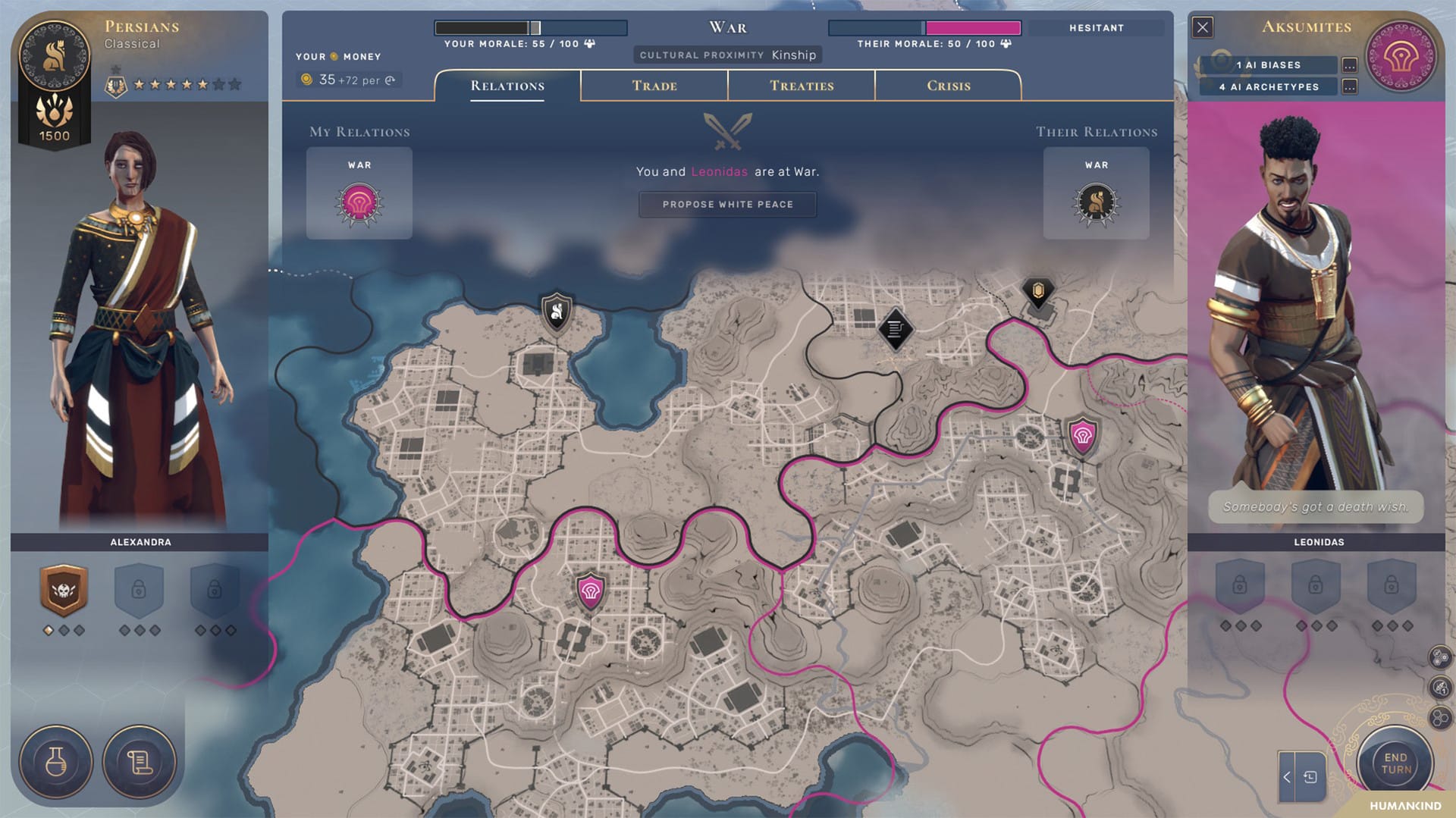

Formed by former Ubisoft developers, Amplitude has been around for a decade now and, in that time, has established a reputation for complex and innovative strategy games thanks to the sci-fi themed Endless Space and its sequel, and the fantasy-themed Endless Legend. With its real-world historical trappings, Humankind – which was released on PC in late August – is the studio’s most overt challenge to Civilization’s 30-year dominance of the domain.

Dyce, who joined Amplitude in 2015 to work on Endless Legend before moving across to Humankind a year later, says that while the themes and smaller scale of their previous games held the Civilization comparisons at bay in the past, this time they’ve been impossible to escape.

‘It’s been surprising the extent to which Civ has featured in conversations. It feels like we’ve been treated in some respects like Civ 7,’ he laughs. The most recent edition of Sid Meier’s series, Civ VI, was released in 2016 and developer Firaxis has as yet made no announcements about development on a 7th instalment.

‘In a certain sense that’s awesome. But in another sense, the ways some people are evaluating it are quite strange to me. It’s like you’re inheriting all this baggage that was never yours. We were criticised in reviews for being both too much and not enough like Civ, sometimes in the same sentence.’

Read: The Elder Scrolls Online and the burden of building someone else’s fantasy world

It’s understandable, of course, that when one game looms so large over an entire genre that other entries into that space will be measured against it. And Humankind, like Civ, presents players with a mostly virgin terrain upon which to build an empire that spans time from antiquity to the modern age. At first glance it looks just like Civ VI, but dig deeper and it has its own distinctive way of doing things.

‘We’re not trying to say the king is dead, long live the king. We’re not looking to replace Civ,’ says Dyce.

‘I think there’s room in that space for multiple players. Humankind is a slightly different take. It’s less monolithic in how it presents culture, perhaps a bit more European in its vision of the world. At the same time, we are attempting to speak to the same audience as Civ. We are trying to put something forward that is not too uncomfortable, that people recognise and yet we’re putting a new spin on it. That’s the tightrope we’re trying to walk.’

SEARCHING FOR A STARTING LOCATION

Back in 2008, Australia’s small game development industry was teetering on its own tightrope. Struggling for an identity as satellite studios of larger (mostly) American publishers and developers, and heavily reliant on jobbing port work and out-sourced projects, development houses in Australia were particularly vulnerable to changing economic conditions. When the Global Financial Crisis hit, it became too expensive for US companies to invest in Australia. They pulled out and many local studios closed.

On the eve of this collapse, Dyce was only 17 years old. He wanted to work in games, but knew the opportunities in Australia were few and far between. He looked overseas instead, keenly aware that he had the advantage of being fluent in English and a second language, thanks to the wise decision of his mother years prior to enrol him in a French school.

‘I’m not saying there was nothing going on in Australia at the time,’ Dyce reflects. ‘But there was certainly a lot less than what was going on in the US, Canada, France… I was a big Ubisoft fan, which is why I ended up in Montpellier. I wanted to work on Prince of Persia!’

He adds, ‘It’s been an advantage to be an English speaker in France who also speaks French. It’s something of a unique selling point. I’m not sure I would have seen the same opportunities open for me if I had remained in Australia.’

Dyce moved to France on his own, at 17, and studied computer science. He is quick to point out that his isn’t some rags to riches story; his parents supported the move financially and he also benefitted from France’s 100% publicly-funded tertiary education system.

After graduating, he bounced between several software companies, making serious games (to aid the rehabilitation of stroke survivors) and not-so-serious games (after a spell programming karaoke Dyce tells me he will die if he ever hears Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky” one more time), before finally landing at Amplitude. Hearing him enthuse about Amplitude and the game he’s just released, it’s obvious he’s found a home at the studio.

‘I’ve been working on [Humankind] for five years,’ says Dyce. ‘Releasing a game feels very much like taking your kids to school for the first time and leaving them with all the other ratbag kids. It’s quite an emotional experience.’

During the development of Humankind, Dyce assumed greater responsibility for the design, switching from a focus on individual systems (military and diplomacy) to eventually managing how everything came together as the game’s lead designer.

‘I was focused on the military and diplomacy, so essentially the things that were inter-player, or interactions between the players. I had a few people helping out–interns–but I was the person responsible for those systems. At the same time, that doesn’t mean you are doing everything.’

‘We had like a strike team, essentially a sub-team of programmers and artists working on the military side. You don’t want to be the designer giving orders from an ivory tower; you need the team to be with you and agree with you. It’s important not to be a dictator. If people feel like they’re merely executing something then they switch off.’

The step up to lead designer on Humankind added more complexity to Dyce’s role.

‘It’s all connected in some way or another. The economy is going to feed into the diplomacy, which feeds into the resources or the combat, and so on. With a game this complex, there’s a lot going on, and you need someone to focus in on the specifics of a given system.’

‘Handing off a system that you’ve been working on, it’s like an extension of your body at a certain point–you know the thing back to front. But I realised that that was what I could best delegate. [I had worked on the diplomacy and military side] whereas I hadn’t been super involved in other systems like the economy. I needed to focus in on that and manage that directly. I delegated what I’d previously been responsible for.’

A TOP-DOWN PERSPECTIVE

Dyce talks through the top-down design philosophy that Amplitude has honed over its 10-year existence.

‘We start with the very highest level concept, a single sentence pitch. “The journey, not the destination” in the case of Humankind. Then we break that down into pillars. For Humankind we had four. 1) Leaving your mark on the world, 2) The tactical use of terrain, 3) Keep the player immersed with interactions that are map-focused, and 4) The historical aspects of trying to be a credible historical fantasy.’

From there, Dyce says the team breaks the game into primary domains or systems. And for each of these, you apply a list of what he calls rationales. So, for example, with the diplomacy system of Humankind, they wanted it to encourage and foster player story-telling. Dyce calls out the term ‘froth’ here, which he says comes from the LARP (live-action role-playing) community where participants are ‘frothing at the mouth’ they’re so eager to relate a story of what happened.

‘You work down from the very vague to the more specific,’ Dyce explains. ‘You make a proposition and then try to validate that. Based on testing, you might have to rework the proposition or the rationales. You don’t decide on a rationale and it’s fixed for all eternity, you iterate.’

The process of iteration continues after launch where the live team takes over and the process of analysing player feedback and preparing content and balance updates commences.

‘At Amplitude, we have this philosophy of focusing on the things players find interesting,’ says Dyce. ‘Right now we’re going through all that feedback and sorting out what’s most important to work on. In practical terms, we have telemetry and player feedback. We have community managers on staff to collect and collate things, to say this kind of feedback has come back this many times.’

Dyce believes it’s good to have a team separate from the development team involved at this stage.

‘It’s a good thing to have that bit of distance,’ he laughs. ‘There’s always a risk for those directly involved in the game to say “You bastard, how dare you?” [The community team] will present things in a quite objective manner.’

Dyce provides the example of Humankind’s stability system – a system designed to steady the player’s pace through the game, penalising them if they try to expand their empire too quickly. One piece of recurring feedback from players is that stability is not enough of a problem in the late game. Looking at the propositions and rationales they had agreed on for the stability system, Dyce and his team quickly realised that it was having the opposite effect in practice.

‘In the case of stability, we wanted it to be so it’s not an issue early on so as not to overwhelm the player. But then it gradually ramps up through the game to become more of a challenge. So when we’re looking at this feedback we can ask are the rationales we proposed actually being respected. If they are, do we need to change them or add new ones? Once we’ve decided on that, we can dig down to the rules and try to work out whether they’re supporting the rationales, or are there some that are letting the side down.’

I ask whether players are more likely to leave feedback about things they don’t like than things they do, and how his team’s analysis takes that into account.

You almost have to remind the team of the good things that have been said. The positive feedback is useful in helping determine what doesn’t need to be changed.

‘The problem when you’re the designer is you see ten positive comments and one negative and your brain just filters out the positive ones to focus on the negative. And so you can find yourself thinking you’ve got to fix that one problem.’

‘But the trouble with that bias is you come to only see the negative. When in fact there is a huge amount of love for the game. You almost have to remind the team of the good things that have been said. The positive feedback is useful in helping determine what doesn’t need to be changed.’

LEGACY TRAITS

In a sign of change of a different kind, Dyce has recently resumed working from the Amplitude office after well over a year of remote work on Humankind. Judging by what I can see through the webcam, there doesn’t appear to be anyone else there and he explains that the return to office is optional for now. ‘My tiny Parisian flat is too small for two people and two workstations,’ he adds. ‘So I’ve moved everything back to the office now that we have that option.’

When asked about his view of the Australian game development scene today, Dyce is understandably a lot more optimistic than he was when he left the country.

‘What I see in Australia now is a lot of locally designed games. Whereas before [global] companies would have their branch in Australia, now you have things like League of Geeks, Team Cherry, House House.’

‘We have a lot of companies now that are Australian-run, they’re from Australia. And that’s a much more healthy and resilient industry than the one we had previously. That gives me a lot of hope.’

‘We have a lot of companies now that are Australian-run, they’re from Australia. And that’s a much more healthy and resilient industry than the one we had previously. That gives me a lot of hope.’

I tell Dyce he used the word ‘we’ several times during that answer, and so I ask if he sees himself as an Australian developer working overseas.

‘At this point, I would honestly say I’m culturally confused. I have three passports. I’ve spent almost as long in France as I have in Australia. I’m a citizen of the world,’ he adds, in a self-mocking tone. ‘Home is where the heart is, right? Australia is the home that I come back to not often enough.’

A few days later, Dyce emailed to say his flight back home to Australia had been cancelled due to a tightening of Covid restrictions in NSW and that he’ll likely be spending another Christmas in Europe.

He’s still hopeful of returning soon.