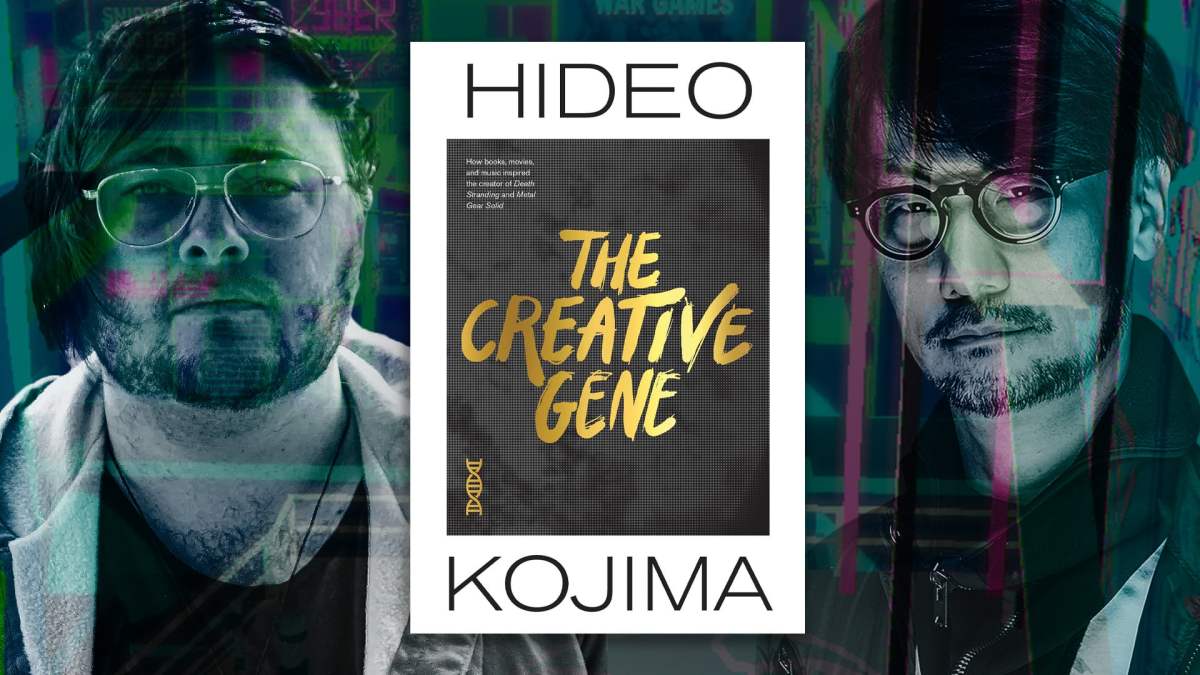

The Creative Gene is a book of old essays by Hideo Kojima, translated into English. It isn’t really worth reviewing as a collection of essays, and I’m not going to explore it as a value proposition for your time. Kojima once described his feeling of going to a bookstore and choosing books blindly as gambling on personal time – and this collection of essays feels much the same. The Creative Gene had chapters that had me staring blankly into the page, while others which had me exclaiming ‘aha!’ every few sentences.

But as a whole, The Creative Gene paints a clear picture of Kojima’s influences – his ‘memes’. All of them. From the inspired to the mundane. If you’re a game designer or any kind of creative, the most important thing you should realise is that your work will undoubtedly be you, and will be made up of the same kinds of things – your memes.

What is a Meme, really?

Knowing a bit about the concept of a ‘meme’ is a necessity going into The Creative Gene. I recommend reading The Meme Machine by Dr Susan Blackmore in order to get familiar with the subject, so you’re able to appreciate the depth of what Kojima’s book really does.

But to summarise memes as a concept: It is the non-biological information we pass on to the next generation. Just like its sibling ‘gene’, memes can replicate perfectly, mutate, or die out.

A clear example of this is language. Language is a meme, but it is also an important replicator of other memes. English has replicated over time in a way where we are able to read old texts, and for the most part, understand everything. But we also see mutation occur.

Words can change, but meanings can stay the same. Sometimes, new words are introduced – YOLO, Pog – to name a few modern examples. Memes are what keeps a culture growing, and we can see this in Kojima’s book, in how intricately his work has been inspired by a great variety of memes.

A Hideo Kojima Game

In art, we boldly claim nothing is new, and everything is inspired. This is the core of what memes are. Once we accept this reality, we are liberated into a form of creativity that allows us to create with the pure expression of ourselves and the strands that surround us. The key here is how works are repurposed, and how memes mutate into their own works.

It might be fun to say Hideo Kojima is the David Lynch of video games. In The Creative Gene, Kojima explains that he refused for the longest time to watch 2001: A Space Odyssey anywhere but a cinema, evoking a response of disdain similar to Lynch and watching films on your iPhone.

But it’s evident that Kojima’s artistic process shares more in common with Quentin Tarantino. In Tarantino’s body of work, we often see iconic shots from the history of film reused specifically to evoke the same emotions on the screen almost half a century earlier, only in a new context – which then often take on a life of their own. In a sense, Tarantino wields the memes of cinema around each new story.

In The Creative Gene, we learn that all manner of ‘selfish memes’ (that is, memes that seek to replicate) have found their way into Kojima’s work. We learn that iconic characters such as The Boss in Metal Gear Solid 3 were born from a story about cats; how the presence of the Walkman and iPod in his games acted as more than just music players – a way for Kojima to project his own personal soundtrack to the world; how characters such as Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle would eventually inform Death Stranding’s Sam Porter Bridges.

It should be clear to most that Kojima wears his influences proudly on his sleeve. If you’ve ever wondered why David Bowie and Stanley Kubrick are often referenced in his work, The Creative Gene details all the reasons why.

Leaving memes for the next generation

For game designers, Kojima provides us with a diary of his memetic expression, and in turn, he passes on this meme to us and asks how we may do something similar in our work.

We don’t have to share the same influences or taste in media he does, but The Creative Gene shows how we can start to think about memes as more than just homage – how we can start to cut away the surface of the things we like, and dig down into the spirit of the ideas that resonate with us.

Many game designers – myself included – carry some of Kojima’s memes in our work. And as game designers, we are encouraged to mutate these memes even further and leave them for the next generation.

Like the example of language mentioned earlier, memes in video game design can just as easily die off as they can mutate. It’s important for us as game designers to assess the progress in our medium that has been made over the last 20 years, and protect this.

In the 1990s, John Carmack proudly exclaimed that story should be a pathway to gameplay (though he’s added caveats to it in recent years). Since then, we’ve seen games do the exact opposite of this, where the gameplay creates a pathway to the story – Bloodborne’s narrative is only subtly revealed through exploration and defeating major characters, for example.

We’ve seen the medium grow, and artistic expression in the space challenged. We’ve seen a changing of the old guard – some of whom now struggle to come to terms with the idea that no one cares about what they think.

Doom was replicated into many different memes: Half-Life, Deus Ex and Duke Nukem. We can see how these three games, for example, would mutate radically into Portal, Prey and Postal and so on, ad infinitum. This is the strength of our medium, where we as designers are inspired by the works before us.

In a sense, the space for games has changed for the better. We’ve seen the memes of game development replicate, mutate, and die out.

The formula for memetic expression is taking something and putting our own spin on it. Nothing is new, after all, so we should embrace this as an artistic reality. When we create, we should apply that ancestry of knowledge to our own works and leave it for players and future game designers to unpack.

Homage and originality

You may get the impression from what I’ve written so far that this is a call for game makers to no longer create new things; that all games should be homages to childhood nostalgia, and that the format for what makes a ‘good’ game was decided in the 1980s. But this isn’t the case, and it’s the exact opposite of what Kojima argues in the epilogue of the book, ‘From Memes to Strands’.

Game development is an incredibly creative space, one which has asserted itself as an art form on par with film or music. Game jams like Ludum Dare and numerous others still give birth to new ideas and form teams that launch successful careers. The Creative Gene does not suggest we abandon this creativity and make everything a safe, marketable clone of every game before the last, but instead, we should embrace memes as strands that bind our shared human experiences.

You may wonder what is meant by this statement – a few paragraphs ago, I said that we should liberate ourselves from these restrictions.

The perversion of this idea can be demonstrated when looking at the homogenisation of the indie space over the last 10 years. If you’ve kept a close eye on it as I have, you will have noticed two memes that have the indie equivalent of the ‘Innsmouth Look’ – a consistent, uniform appearance and behaviour. There are pixel art platformers, where the main protagonist looks like a graphic designer, and PlayStation One-style horror games, that kinda just boil everything down to looking like a hotdog.

I bring these up not to lambast anyone creating games in this genre, but to raise the idea that when you see these games scroll past on your social timeline or store directory, it’s almost immediately obvious which games are referencing other memes.

We see games that are replicating memes of designers – something which is inseparable from who they are, and the work they do. We also see games that are made to assimilate into a genre, to make a quick buck. The latter example consists not only of designer memes, but also memes concerning the idea of what an indie game is, or should be. This in itself is a perversion of indie games.

The Netflix series Stranger Things is another example. Rather than being an earnest reflection of the creator’s youth, I see it instead as a collection of safe, marketable memes. It combines a hit list of 1980s culture and ties it together with beats from a Steven King story. Compare Stranger Things to Midnight Mass, which has a similar 1980s pulp tone to its story, but is not actually set in the 80s. It doesn’t disrespect its main character with plot armour, and never references events while looking directly, and knowingly, at the camera. It is instead an excavation of religion, spirituality, death, life and cult with personal reverence.

I watched Midnight Mass with my father-in-law, who grew up Catholic. My family, on the other hand, moved to Australia following the empty promises of a 1990s Christian cult. Our interpretations of the sinister motives at play were widely different, yet despite having these different upbringings, we were connected to the plot in a way that was hard to describe. I would explain how certain characters were similar to the underlings of a brainwashing cult leader, and he would explain what Ash Wednesday represented.

These memes were present in our different upbringings and were meaningful enough to create a strand between us. To have strands in your work is to be able to look at how the lives of memes, as they exist in media and the world, are connected.

As I said previously, if you are a game designer or any kind of creative, The Creative Gene pushes the idea that your work will undoubtedly be you and your memes, and embracing them is what becomes your signature as a creator – something that will hopefully then connect with others to live on and replicate.

If you are simply a video game enjoyer, The Creative Gene will likely posit that the phrase ‘a Hideo Kojima Game’ is not simply self-aggrandizing marketing, but rather a statement of memetic integrity, and that there are a multitude of reasons different directors come to embody their signature methods of creation.