I’m not getting into it, but complex (or even simple) notions of gender in video games have a long, complicated, and largely grotesque history.

At the same time as this history was playing out, the video game industry was developing its norms and processes. When it comes to discussions of video games in media, especially reviews and previews, focus often sits at the intersection of gameplay and narrative, missing out on other aspects key to the experiential reality of playing video games.

This is why reviews like those for family games that contain the experiences of multiple family members or that focus on the accessibility of a game are so distinct; they sit outside the genre expectations of a game review.

From this restriction, and paired with gaming’s gender-hampered past, reviews often leave out the ways games can engage players in expressing and experiencing their gender. When we discuss gender expression in games, we often seem restricted to talking about a process of one-to-one identification. Where an individual player relates to characters directly. But gender – and more specifically gender expression – is not so simple.

Interactivity allows for a process of embodiment and enactment, rather than simple identification. Gender embodiment, to feel fulfilled and as if you are enacting your own definition of what your gender is to you, in video games is made not only by narrative, but by aesthetic, mechanic, and contextual components.

A good example of this is the user interface (UI) in Life is Strange. The uneven, hand-drawn, style of the button prompts is not inherently gendered, evoking an art school style that wouldn’t be out of place in a game like Scribblenauts (which conveys an age grouping more than a gender).

At PAX Aus in 2023, one of the winners of the Aus Indie Showcase was Copycat, which describes itself as a mix between Stray and Life is Strange. The game carries a similar central gameplay conceit as Stray – that being: “you are cat mmmmm isn’t that fun.”

But where Stray’s user interface reflects the chic, techno-futurist aesthetic featured in the rest of the game (one usually connoted with masculinity), Copycat opts to adopt the aesthetic of Life is Strange in its user interface. The sketch-like scrawl of the UI conveys not only an association with the genre that Life is Strange helped to popularise in the 2010s, but with its focus on femininity, too.

Read: ‘Copycat’ is much more than just a cat game

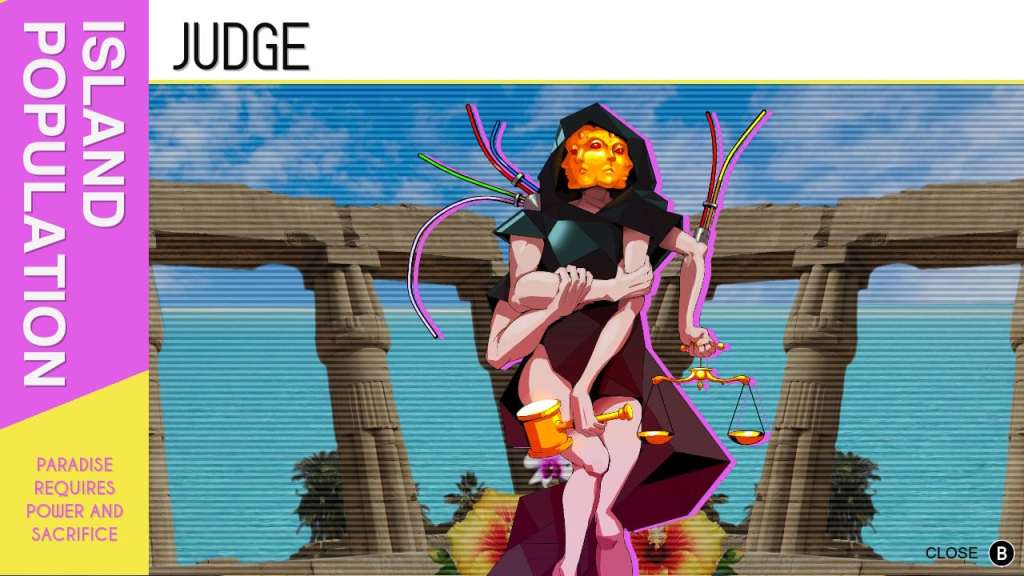

Conversely, the user interface and context of a game like Paradise Killer can work into and against our understanding of the culture around gaming. With a heart-filled, fluoro-pink vaporwave aesthetic, it leans into several 1990s callbacks – not only in the way the characters seem to be little more than cardboard cut-outs, but the casualness of the leering.

Everyone’s static pose is stretching; biceps are flexed, chests are out, honkers: exposed. The hyperfeminine interface works against the sexuality depicted in the game. We are so used to UIs with hearts in them being relegated to ‘girl games’ (used derogatorily to mean something simplistic and often sexless) that for a heart-filled UI to sit next to a horny, violent murder-mystery with a sci-fi aesthetic, it calls into question our gendered associations.

To think of games’ relationship to gender, and more specifically the level of gender expression we ourselves as players can experience from playing games, as simply a literal process of identification, limits our engagement with the joys of an interactive medium. Thinking that individual gender can take form in games in non-literal ways, and including it in our discussions of video games, allows for new ways of talking about the construction of identity by, and engagement from, players.

Players are not restricted to choosing how they express themselves, based on the characterisations determined by developers (which are subject to whim and trend).

Of course, queer and feminist narratives in video games are not in so robust a shape as to warrant no further attention (trans-inclusion in games especially still has a long way to go). But our focus should not be solely focussed on including more diverse voices in the narrative and media surrounding games. We should also look at how we can reshape our expectations of games media, and the structures that have come to exist around it.

This article was commissioned by GamesHub and Creative Victoria as part of Wordplay, a games writing mentorship program held during Melbourne International Games Week 2023.