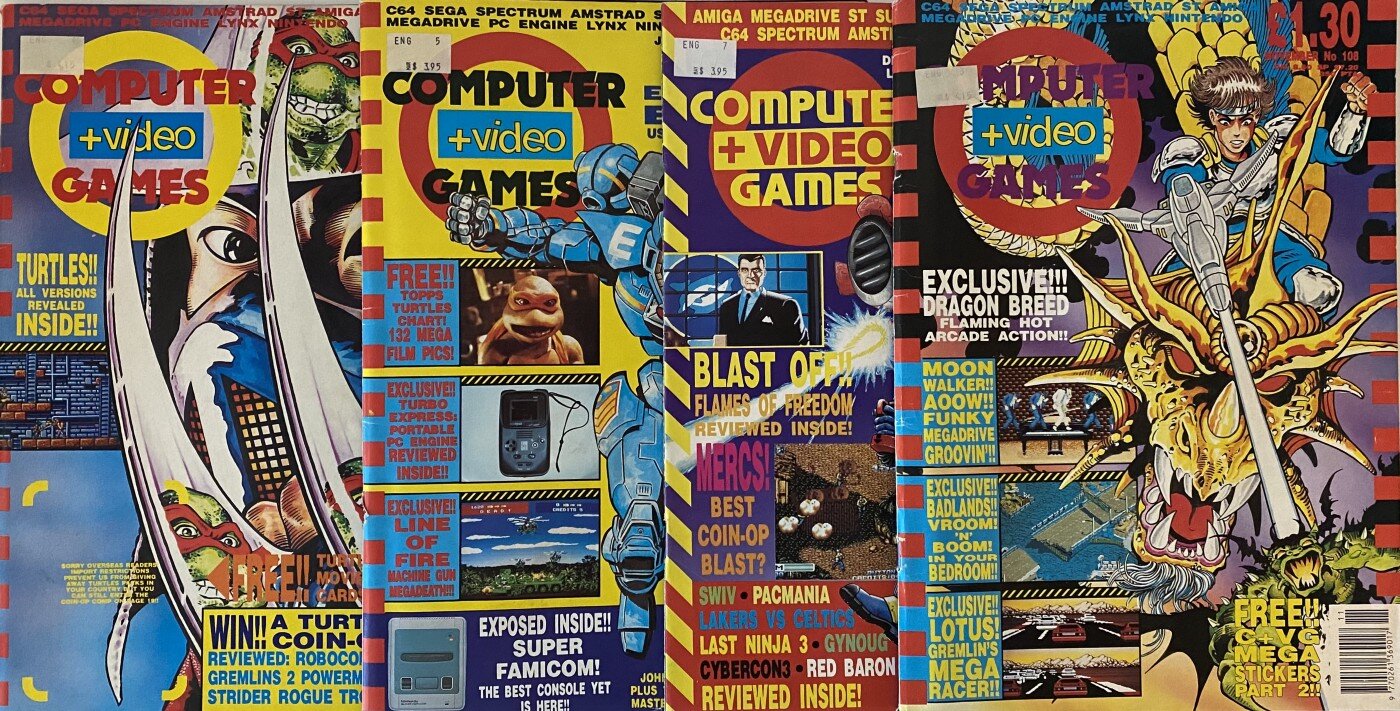

At the start of the 1990s, Western video game magazines were scrappy, juvenile, and filled with images of animal mascots bouncing through colourful 2D levels. In other words, they were a snapshot of the broader gaming industry at the time; one dominated by 12-year-olds kids playing Mega Drive and Super

Sony’s efforts to hitch the new PlayStation console to the emerging UK club scene would forever change the perception of gaming, and much of its public-facing image. Led by UK publications, it would filter down to other countries like Australia via the numerous import magazines on local newsstands.

The land before time

The original PlayStation was launched in Japan in November 1994. It made its way to Western markets a year later. It predated the Internet as we know it, smart phones, music streaming, and everything else we associate with the ‘modern world’.

It was a different time and place. In this era, video games were still seen as something kids played, and the pages of UK magazines like Mean Machines and CVG reflected that. A quick glance at a random issue of Mean Machines from 1992 reveals editorial pages filled with crude jokes about bowel movements, the ‘Mean Yob’ advice column, and reader illustrations of Sonic decapitating Mario (or vice versa).

This is where Sony saw its opportunity. The PlayStation wasn’t just a ground-breaking console technologically; it was an attempt to expand the whole industry culturally. By targeting an older, cashed-up demographic, Sony hoped to take video games to a bigger, mass-market audience.

But to do that would require video games shedding their ‘kids image’. They would also need to do something even more ground-breaking – become cool.

3:00 AM eternal

Geoff Glendenning was a young marketing manager at Sony UK in this era – one with his finger on the pulse. As a 9-5 salary man who was also familiar with the illegal raves that were popping up throughout the country in the 1990s, he was uniquely placed to help worlds collide.

As he explained to the Guardian, ‘In the early 90s, club culture started to become more mass market, but the impetus was still coming from the underground, from key individuals and tribes.’

‘What it showed me was that you had to identify and build relationships with those opinion-formers – the DJs, the music industry, the fashion industry, the underground media.’

To capitalise on this trend, Sony created ‘chill out’ rooms showcasing the PlayStation in clubs throughout the UK. But while that stunt helped get the new console in front of wide-eyed eyed clubbers at 3am, it was really a PlayStation launch title named Wipeout that sold the product.

Developed by Psygnosis, Wipeout was a stylish, futuristic racing game with a soundtrack featuring the likes of the Chemical Brothers, Orbital, Leftfield and other heavy hitters from the UK club scene. With branding developed by the Designers Republic – one of hottest design agencies in the UK at the time – Wipeout managed to capture the look, feel and sound of the mid-1990s underground, and package it up as an easily accessible and entertaining consumer product people could take home.

Wipeout’s presence in UK nightclubs gave PlayStation grassroots credibility, and allowed the company to action the second part of its mass-market campaign. This was made possible by the deep ties Sony already had within the broader pop-culture ecosystems, thanks to the work of its existing music, film and entertainment divisions

This created an opening for its PlayStation division to reach media in a way that rivals like

According to Glendenning, Sony’s marketing efforts, ‘Took the age of the average gamer from about 14 to about 23. It made games cool, it made them part of popular youth culture – people were no longer embarrassed to admit they played them.’

Arrested development

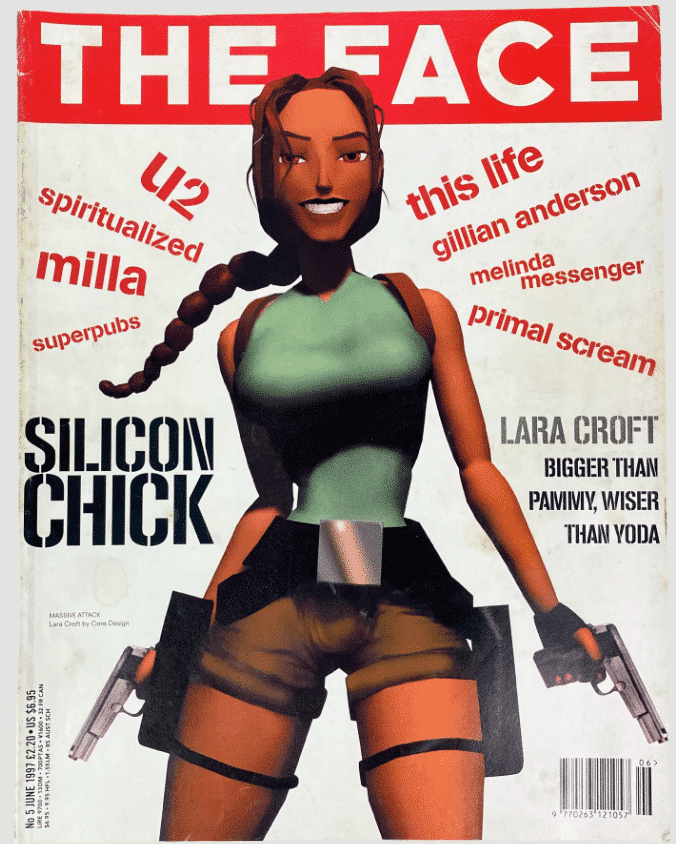

While gaming and the club scene were cosying up to each other in the mid 1990s, they weren’t the only cultural movements that were taking place. The mid 90s also saw the rise of Brit-pop, ‘Girl Power’, Cool Britannia, New Labour and the arrival of ‘Lads’ magazines – ideas which were exported to the rest of the Western world.

This new generation of men’s magazines were an attempt to package up ‘sex, sport, gadgets and grooming tips’ for a newly defined male demographic. They were also the jumping off point where a 16-year-old might graduate from Mean Machines and Mega Drive to FHM and articles about ‘How to pull a bird’ alongside coverage of games, music and movies.

Gaming magazines and their publishers weren’t blind to all this, and responded in kind. They reasoned that if men’s magazines could cover gaming, they could expand their scope as well.

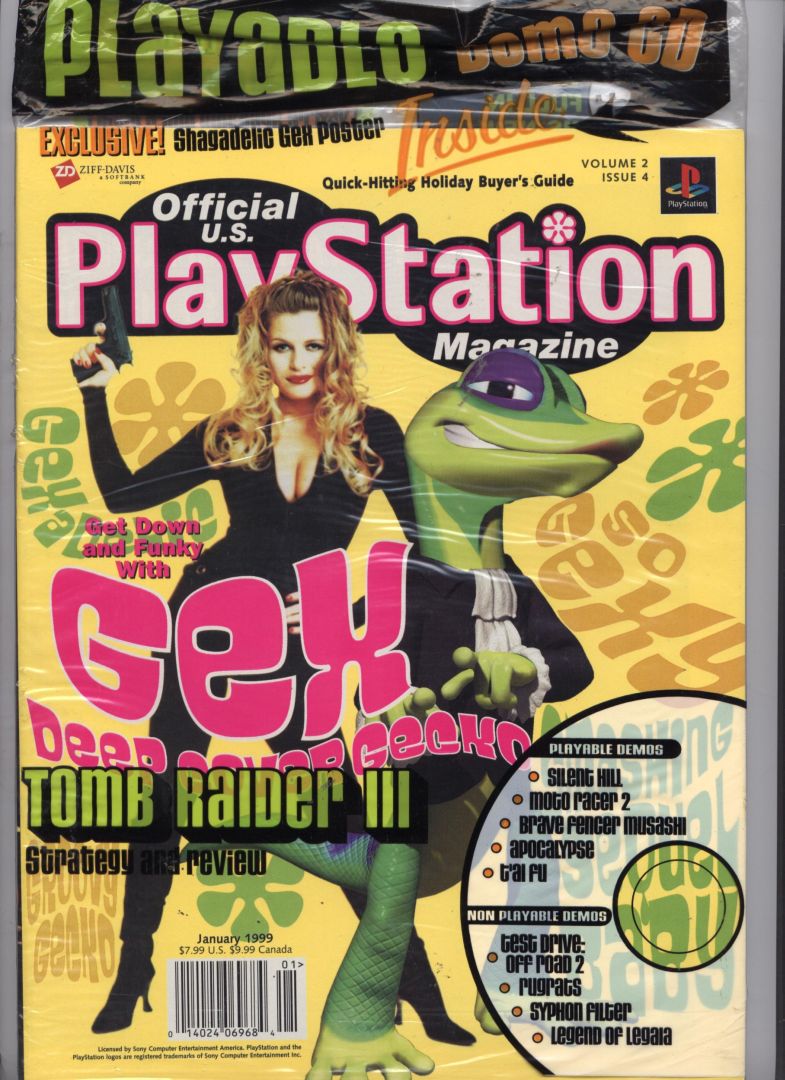

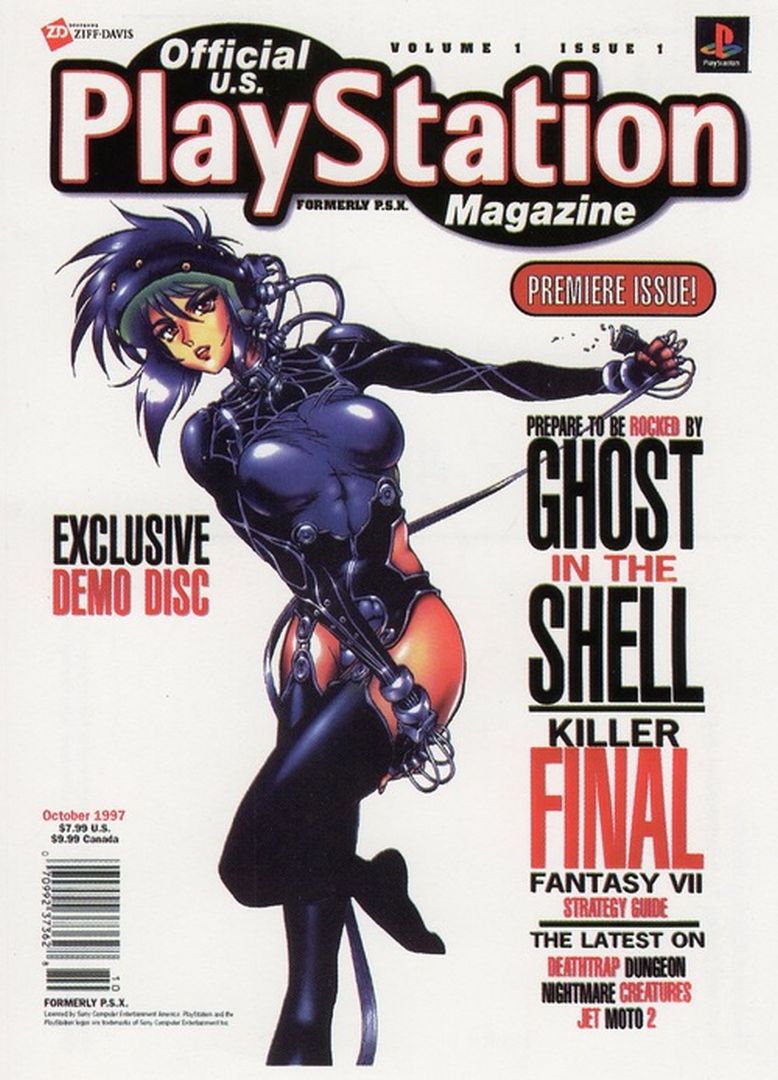

As Paul Glancey, founder and editor of MegaTech once explained to me, ‘Sony took games fully into the mainstream and magazine publishers started chasing a new audience. Some games magazines tried to appeal to more casual readers, who were more interested in free gifts or demo discs.’

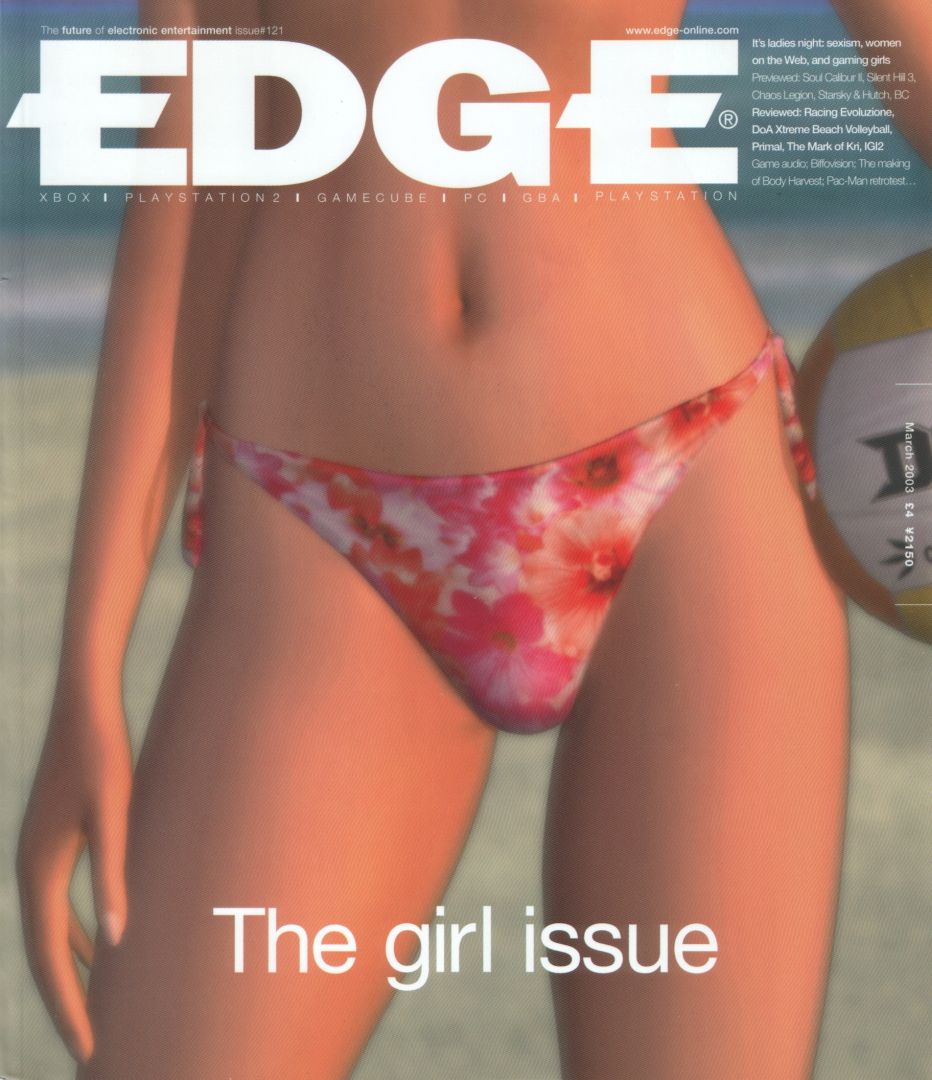

‘The supposed ageing-up of the audience and the rise of lifestyle “lads mags” like Loaded and Maxim also had the effect of giving editorial teams apparent licence to use more expletives, more football references, and more pictures of young women in lingerie,’ continued Glancey. ‘This changed the tone of magazines, with the result that they became a low-budget, teenage boy’s idea of a more grown-up publication.’

Pre-millennium tension

What began as a gradual shift in tone for gaming magazines started to gather momentum as the decade progressed. This was reflected in the design and layout of the magazines as much as the actual content.

As the Internet began to make its presence felt, and the new millennium drew closer, it felt like culture itself was accelerating. The lines between the old world and the new world just over the horizon began to blur, and that sense of chaos and uncertainty manifested itself in increasingly busy page layouts.

Meanwhile, the next generation of kids was coming through, and the gaming magazines they were picking up for their PlayStations had a very different look and feel to the publications that Mega Drive and Super

The world had changed. Sony had taken gaming out of cloistered homes, and expanded both its scope and audience. In the process, it had shifted the creation of gaming publications, giving them licence to adopt a new tone and attitude; an uneasy middle-ground between childhood and adult.

Gaming had officially entered its awkward teenage years, thanks to this monumental shift.

This article has been retimed since its original publication.