I Was a Teenage Exocolonist is a genre-defying life simulator with a literal twist in time.

You play as Sol, a child born ‘among the stars’ halfway through a 20-year voyage from Earth to a planet on the other side of a wormhole at the edge of the Milky Way. Arriving on Vertumna on your tenth birthday, the game follows Sol over a decade of their teenage life, the course of which largely depends on the actions of the player. As the playfully light novel-esque title suggests, I Was a Teenage Exocolonist is a game as much about childhood as it is science fiction fantasy.

The Game of Life

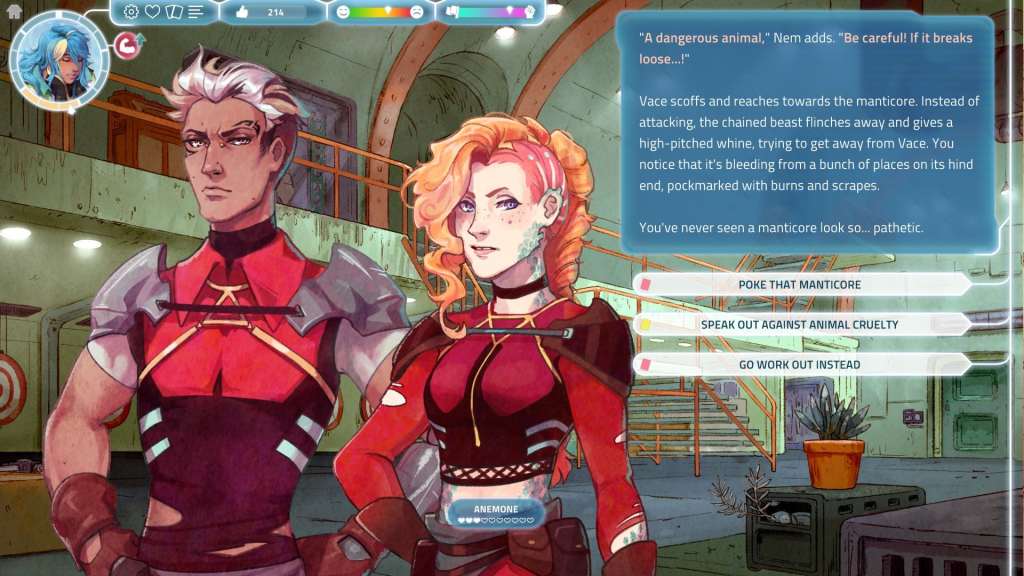

Exocolonist is primarily a stats-based game; over the ten years of the game’s story, Sol can develop their identity and skillset along with physical, mental and social abilities. Different life experiences award cards that represent individual memories, from winning a trivia competition to sneaking outside the confines of the colony walls with your childhood friend. These cards form a deck used to overcome various skill challenges via a poker-like mini game, but like Supergiant Games’ Pyre, success in these challenges is not integral to completing the game.

Whether or not Sol succeeds or fails simply nudges the narrative in a different direction. Sol could lose every challenge in the game, and that itself would be a valid experience of I Was a Teenage Exocolonist’s story. Acquiring these cards through Sol’s childhood experiences also lends a kind of nostalgic significance to each card, particularly early in the game when your collection is small and each experience of Vertumna looms large in Sol’s memory. As you progress through the game and acquire more experiences, the individual significance of each memory lessens as they accumulate into the equivalent of a body of knowledge – the fruits of a life lived, in whatever form you chose as a player.

I Was a Teenage Exocolonist is a game that asks the player to reflect on the impact of humanity and technology on the environment, and Sol is regularly asked to engage with the politics of the colony. Described by developer Sarah Northway as ‘sort of a multinational hippie commune with a colony ship’, the Vertumna colony is a utopian project born of big dreams that still strays at different points towards capitalist and militaristic philosophical directions.

Exocolonist asks the player whether these malaises are inevitable, and reiterates that they are not, but you as the player need to put in the work if you want to overcome them. Even if you try your very best to avoid doing anything at all, Sol cannot escape being a part of Vertumna and will always be looped back into the fray, in one way or another.

I Was a Teenage Exocolonist rarely lets you exist as a passive citizen for long.

The Art of Failure

One of the most compelling elements of the game is revealed gradually in an initial playthrough. As a child, Sol is plagued by strange dreams and visions, some of which seem prophetic and others that are disturbing and shadowy alternate histories. Over time it becomes clear that these dreams are fragmented memories of different iterations of Sol’s life.

Vertumna seems contained to a single instance of time in which Sol exists, again and again, and is the only one (seemingly) who recalls each repetition with any clarity. Pursuing an answer to why this is occurring is one possible path Sol can follow, but they do not need to. Sol’s visions are their memories of your alternate playthroughs, and what you do in each can slightly alter the course of the next. What you do in one life may or may not change much now, but it might mean everything to the future.

I spent hours of my second playthrough working towards a specific goal – learning the source code of the ship’s advanced AI, Congruence, so I could stop the shields from failing. In the best possible outcome, the loss of hydroponics leads to famine. Having learned the source code, I booted up a new playthrough to excitedly see the different directions the game might take, only to laugh in shock. Sol could recall the source code to the AI from their dreams but, of course, had no idea how to recalibrate the shields themselves – having never interacted with that part of the ship’s engineering in a past life.

I’ve rarely felt such a sense of amused delight and horror at an event in a game, to have something make such an obscene amount of logical sense – and be such a reminder of my player hubris. How indeed could I learn to recalibrate the shields? The answer was even better – the only way Sol encountered the required knowledge about the shields of the Stratospheric was if Sol failed or ignored a path I had relentlessly pursued during my other playthroughs.

Sol needed to cumulatively experience failure and success to have the option to completely prevent food scarcity in the future. Perhaps more powerfully, I needed to let myself explore, try, and fail the different parts of the game to understand its story completely. For many role-playing games I’ve played in the past, information was only revealed through ‘correct’ exploration of the game’s world. That Exocolonist nudges you towards failure and makes failing an integral part of the experience seems a gesture that struck me as expressing something deeply about both the story I Was a Teenage Exocolonist wants to tell, and about the act of gameplay itself.

There isn’t a stated ‘ideal’ ending to Exocolonist, because all the endings happen, but the implication is that the ideal ending each player personally finds solace in is always and only a result of the trials and failures of all the others.

I Was a Teenage Exocolonist uses a moment intrinsic to play, failure, to explore an idea about effort that seems particularly salient in the context of our present environmental moment. Focusing on an individualistic experience of time is not enough. Exocolonist values time on a grander scale – time where you plant the seeds you yourself will never see become trees – and points out the flaws and limitations of seeing your actions only in the context of a single lifetime. If Sol tries to solve a problem now, even if they fail, the effort made is recognised and valued by another life.

The Human Experience

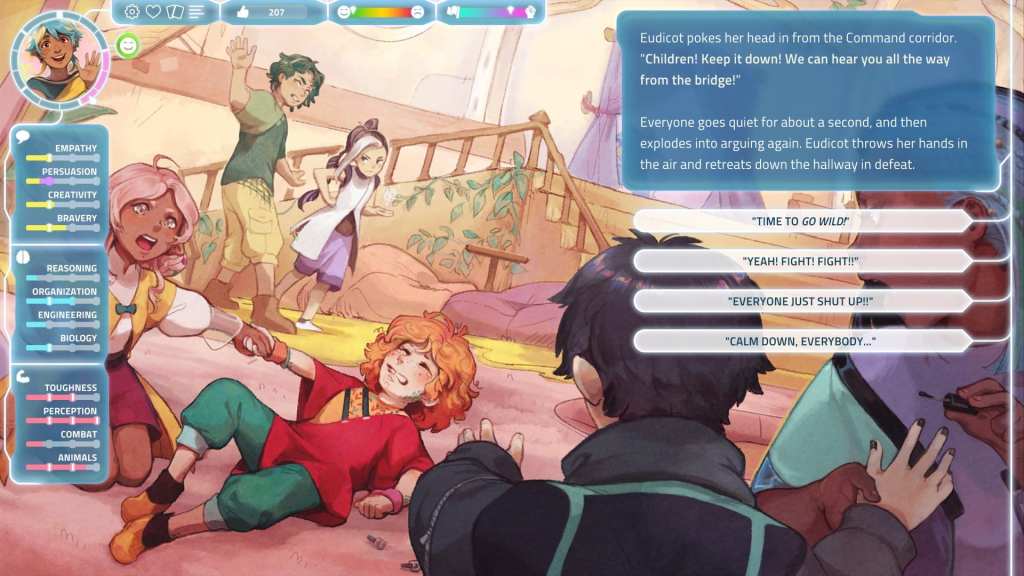

I Was a Teenage Exocolonist is an intriguing game based on its clever and playful approach to game design alone; using failure and repetition as essential and valuable components of what it means to make a home, and the effort to do it right. What makes it an excellent game is the brilliant writing of and interactions with its central cast of characters, predominantly made up of other children born on the Stratospheric colony ship during its 20-year voyage. Each character serves as a microcosm of the game’s broader philosophical questions about what is to be human and not human across numerous everyday interactions, deconstructing the concept of the human being in a way that makes Exocolonist a compellingly personal posthuman narrative.

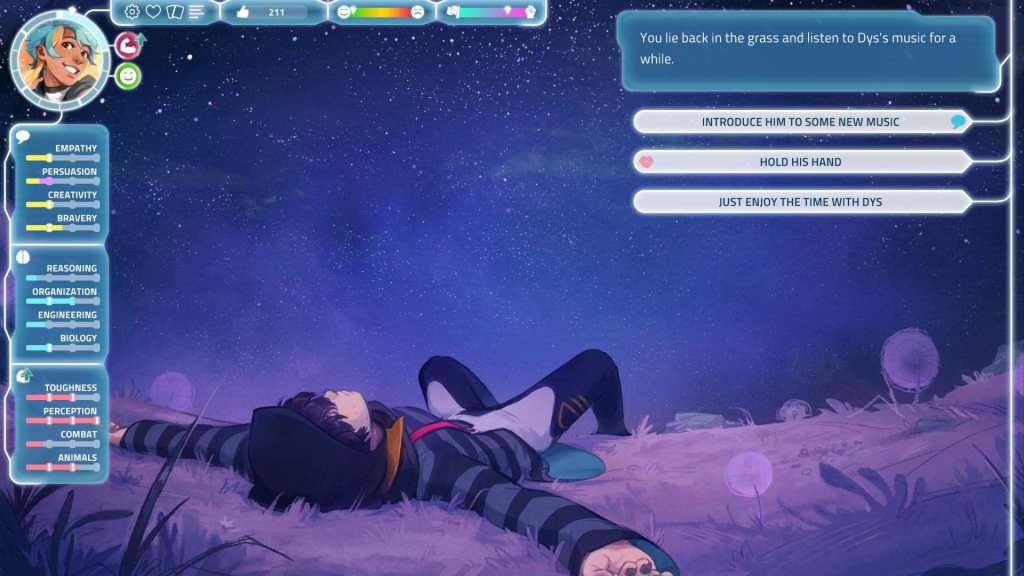

Across all my playthroughs, some of my favourite interactions were with estranged twins Tangent and Dys. Divided after the loss of their mother at a young age, Tangent and Dys’ experiences and storylines share similar beats, but play out across vastly different spaces and experiences. All the children of the Stratospheric who grew up alongside you have a genetic mutation that enhances their physical or mental capabilities but fundamentally alters their experience of the world. Most of these enhancements are subtle genetic shifts, rather than ‘superhuman’ abilities, and affect their experiences on an everyday (rather than grandiose) level. Tangent requires less sleep than a normal human, and Dys feels no fear. Being free of such deeply entrenched human experiences changes who and what Tangent and Dys are fundamentally. Who are we if we don’t need to sleep? Are we human if we feel no fear?

Dys, in particular, experiences deep feelings of ostracisation from other members of the colony even as a young boy, and the game subtly makes the player reflect on how much that is a result of the adult colonists unease with the uncanny child who is scared of nothing. In my playthrough, I came to feel it was this unease with Dys’ posthuman self (which the adults themselves created) that leads to parentless Dys’ slipping through the cracks of the colony’s social order.

Dys’ lack of fear makes him less amenable to measures of control by fear – starting with ‘harmless’ ideas in childhood (such as ‘the environment outside the walls is dangerous, so you shouldn’t go there’) and more dramatic political efforts to control the population by fear in the colony’s later years. For all their utopic dreams, the adults born and raised on earth are unable to relinquish using fear as a method of control, but Dys always exists as a foil (albeit a recalcitrant and challenging one, even for the player).

Invitation to Vertumna

I Was a Teenage Exocolonist is a game filled with incredible love and joy for its characters, the story it wants to tell and the artistic medium of the video game. Its writing, art and music wondrously capture the intensity of childhood and of being a teenager.

Simple, thoughtful touches that make the game more pleasant and accessible are there for the player benefit without fanfare or fuss. For a game filled with intense and challenging personal experiences, there is a list of warnings in the menu that can be viewed with and without narrative spoilers. It’s easy to change everything about your character’s looks and gender at any point in play, the song and artist of each piece in the soundtrack is visible through the main menu, and you can change the music at any time. The difficulty of the card-based mini-game can be changed at any point, as can the introduction of an autoplay feature that keeps the stat-based mechanic but allows the player to focus on the story (or play the game quicker, for those with limited time).

These small efforts to make the experience enjoyable mean the mechanics of the game receded as I played, allowing me to immerse myself in Exocolonist’s narrative and philosophical reflections. I Was a Teenage Exocolonist is a beautiful game, a synth-laden ode to growing up and allowing yourself to fall, fail, succeed and explore in a posthuman world that asks thoughtful questions about what it means to exist alongside the natural environment.

5 Stars: ★★★★★

I Was a Teenage Exocolonist

Platforms: PC, Mac, PlayStation 5, PlayStation 4, Nintendo Switch

Developer: Northway Games

Publisher: Finji

Release Date: 25 August 2022

The Mac version of I Was a Teenage Exocolonist was played for the purposes of this review.